Investor Insights

SHARE

How can we ensure affordable housing?

As I note below, solving housing affordability won’t be enough with just a massive supply of affordable dwellings rapidly built by state and federal governments. The market for these properties will have to be tightly regulated, and controlled, with continuous maintenance and updates. It’s doable, as is its financing.

The protected species: residential real estate owners

If you’ve been following the blog for the last decade, you will know I have argued residential real estate owners in the country are a ‘protected’ species.

Whether it’s negative gearing, zero capital gains tax on primary places of residence, stamp duty concessions, the $25,000 homebuilder grant or the First Home Owners Grant, there isn’t a government policy that does anything other than help support property prices or at least prevent any kind of crash.

And if we consider our entire financial system, it’s built on the back of loans to fund property purchases. That means not only has the government incentivised people to buy property (and therefore doesn’t have any incentive to see prices decline), but the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Council of Financial Regulators, and the banks are all aiming to maintain stability in the financial system by avoiding, at all costs, a collapse in house prices.

The illusion of first homeowners grants

So, if you’re an economist or a commentator who believes property prices could fall 30 or 40 per cent, you’ve not considered the real underlying drivers.

The First Home Owners Grants offered by the states is a particularly humorous attempt to make housing more affordable.

In Victoria, the $10,000 grant is available to those buying or building a home valued at up to $750,000. In New South Wales, $10,000 is also available to those purchasing an existing dwelling up to $750,000, or a new build worth less than $600,001. Up north, in Queensland, $15,000 is extended to those buying or building up to $750,000, while in Western Australia, a $10,000 grant is provided for purchases up to $750,000 or $1 million, depending on location. In the Northern Territory, various incentives are available including a $10,000 grant, the First Home Guarantee, which supports eligible purchasers to buy with a deposit of as little as five per cent and as little as two per cent for eligible single parents. Meanwhile, in South Australia, $15,000 is offered for purchases up to $650,000, and finally in Tasmaia, first home buyers receive $30,000 for the acquisition of a property of any value.

Consider giving everyone in Australia a First Share Portfolio Buyers Grant, or a First Car Buyers Grant; prices would surge. It’s inevitable. If you give people more money to buy something, the price rises. We gave everyone money during the pandemic and are now dealing with inflation. You don’t need a PhD to work that out.

In the last decade, Australian state and federal governments have outlaid $20.5 billion for various first home buyers schemes. What do you think happens to a property market if an additional $20.5 billion is injected into it? It only helps to accentuate the influences already pushing property prices higher. Of course, it serves the government, the financial regulators and the banks. But it doesn’t serve those who cannot afford to buy in the first place.

Henry George and progress and poverty

During the 19th century, American political economist Henry George made a profound revelation regarding the unprecedented surge in industrial output, which, in turn, led to an escalation in urban land prices. As landowners reaped substantial windfalls, a tumultuous wave of land speculation and real estate bubbles ensued, triggering an era of volatility and uncertainty. The Gilded Age saw the accumulation of vast fortunes by industrialists, bankers, and landowners, but it coincided with a surge in poverty, inequality, and societal unrest.

Singapore’s housing system: A solution to affordable housing?

Sound familiar?

In 1879, Henry George boldly presented his critique of the capitalist system in his seminal work, Progress and Poverty (1879). Progress and Poverty, achieved global acclaim with millions of copies sold. It delved into the perplexing paradox of rising inequality and poverty amidst remarkable economic and technological advancements. George advocated for solutions to social issues caused by extreme greed, particularly concerning the laborer’s who contribute real economic value through their hard work in production. Among these remedies, George proposed implementing rent capture measures like land value taxation, where higher taxes are imposed on more valuable land.

What would widely be regarded today as going too far, George’s thought-provoking stance proposed a radical concept: the communal ownership of land, with society collectively benefiting from any upsurge in land rents. The daring proposition that lay at the heart of his proposal was a single tax on land values, the idea being that by taxing land values, society could recapture the value of its common inheritance, raise wages, improve land use, and eliminate the need for taxes on productive activity.

The mechanics of Singapore’s housing scheme

While it challenged convention and is arguably anathema to capitalism, it nevertheless draws attention to the structure of our society and should still promote debate about a fairer, more equitable one.

Singapore has attempted to deal with the issue, with what appears to be a nod to George. Singapore today enjoys a very high homeownership rate of 91 per cent, and the government’s involvement in the housing market is extensive and unique. Despite one of the world’s highest concentrations of millionaires and one of Asia’s most expensive housing markets, young newlyweds can easily afford to buy a well-located property close to their place of employment.

Financing Singapore’s housing scheme

This is possible because the Housing and Development Board (HDB), a statutory board of the Ministry of National Development, is the largest housing developer. It is important to note, however, that in Singapore, more than 75 per cent of the land belongs to Singapore Land Authority (STA), while the remaining freehold land belongs to statutory boards like HDB, JTC, PSA and other private owners. There are three land ‘ownership’ types: 99-year lease, 999-year lease and freehold.

Established in 1960, and superseding the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), the Housing Development Board was tasked to solve a housing crisis by rapidly increasing the supply of homes for the poor to rent. By the middle of the decade, it had housed 400,000 people.

The dual property market in Singapore

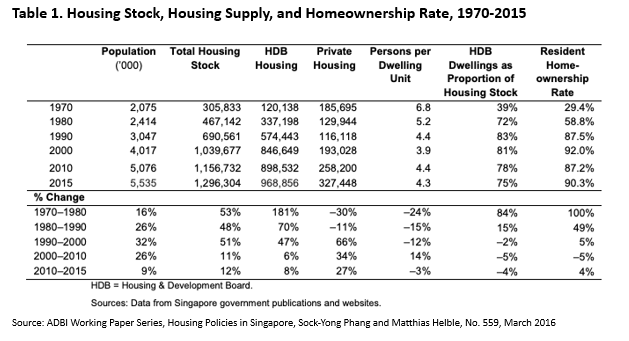

In 1960, just nine per cent of Singaporeans lived in rental public housing. In 1964 the decision was made to offer subsidized flats for sale under the government’s “Home Ownership for the People Scheme”. By 1985, four-fifths of the resident population were living in HDB flats. Today, more than 90 per cent of HDB’s housing has been sold – at below-market prices – on 99-year leases to eligible households. Singaporeans typically purchase their first home from the HDB, and buyers can sell their HDB flats in an active secondary market at market prices only after five years. The pace of supply can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Housing Stock, Housing Supply, and Homeownership Rate, 1970-2015

Applying lessons from Singapore to Australia

A quick look at www.propertyguru.com.sg reveals genuinely well-located (everything is close to the city in Singapore) HDB flats for sale for S$550,000, alongside opulent S$30 million penthouses and colonial-era homes that have sold for as much as S$220 million. And remember Singapore’s HDB was set up in 1960. Even after 63 years, inner-city apartments are still available for S$550,000. It’s also worth noting the buyers of affordable HDB flats don’t treat them like slums, they take great pride in property ownership, often renovating with the assistance of professional interior designers.

HDB apartment blocks are meticulously designed. Each cluster of buildings are communities, with essential amenities such as playgrounds, food centers, and local shops. More recent developments include health clinics, community centers and libraries. Importantly, the management of these estates is integrated into comprehensive servicing policies that incorporate the city’s transport system and racial integration.

Perhaps in its appreciation of George’s 1879 trestise Progress and Poverty, Singapore acknowledges that HDB homes represent the most significant stake its citizens have in the country’s prosperity. Consequently, the HDB maintains its buildings and grounds and periodically upgrades them. Residents and businesses pay for maintenance, maintenance is carried out by Town Councils and their funding comes from government grants.

At the end of the 99-year lease, the dwelling is practically worth S$0 and the resident (usually a second-generation occupant who didn’t pay for the apartment) is no longer given the right to continue living in the apartment and can apply to buy it or another. Typically, after an HDB apartment turns 39 (with 60 years left), buyers tend not consider the unit, because Central Provident Fund (CPF) usage to pay for the house is restricted, and bank loans are tightened. While Singapore is yet to see any HDB units’ leases expire, it is expected interventions, such as a renewing of the lease for a fee, will occur.

In 2020, Singapore had more than a million HDB flats, sold at least 16,600 new apartments and had another, almost 70,000, under construction.

Financing the scheme in Singapore

To finance the scheme, the HDB provides up to 25-year mortgage loans, at an interest rate of 2.6 per cent. Homeownership is financed through CPF savings.

Most public housing in Singapore is lessee-occupied. Under Singapore’s housing leasehold ownership program, housing units are sold on a 99-year leasehold to applicants who meet certain income, citizenship and property leasehold ownership requirements. The estate’s land and common areas continue to be owned by the government. HDB prices are below market prices, and buyers enjoy additional discounts in the form of housing grants calibrated to incomes. Subsequent sales of HDB flats in the private market originally had to be to buyers who satisfied the requirements for purchasing new flats. Since 1978 a resale levy was implemented.

The HDB also provides public housing for rental, mainly for lower-income households and households waiting for their purchased flats. Rental public housing has lower income requirements than lessee-occupied public housing. Meanwhile, the government also sells land to the HDB, and fully finances its annual deficit.

Within Singapore’s housing sector, there is a high degree of progressive taxation. Higher-income households, foreigners, and investors pay market prices, implicitly higher land taxes, higher stamp duties, and are subject to higher rates of property taxes. And for those who might immediately recoil at the thought of higher taxes, they haven’t prevented some properties commanding the highest prices in the world.

Challenges and future plans

The system isn’t perfect – property prices continue to rise and solving the end of the 99-lease issue appears pending. According to Wikipedia “On 4 October 2022, The Minister of National Development, Desmond Lee, elaborated further on the government’s policies to intervene to keep public housing relatively affordable and available. In hopes of cooling the housing market, the government plans to implement a fifteen-month waiting period before homeowners can buy an HDB resale flat, continued supply of significant grants for first-time buyers, and tightened maximum loan price limits. Likewise, to keep providing a counter to the resale market, the HDB ramped up its Build-to-Order supply, which is on track to place 23,000 apartments on the market between 2022 and 2023.”

Whatever your views, it is clear, however, a dual property market exists in Singapore.

If Australia’s government is serious about making housing affordable, it needs to stop handing out grants for buyers to meet market prices, which only fuel further increases. It must consider a dual market approach with one market supplied, controlled and regulated by the government.

As an aside, there is no First Home Buyers Grant offered in the Australian Capital Territory, and coincidentally, it has been the worst-performing real estate market during the latest sell-off in prices and has recovered the least in the more recent recovery.

Does that make Australian Capital Territory property more affordable?

Maybe Victoria thinks so. That state is considering following the Australian Capital Territory and scrapping its First Home Owners Grant scheme. Before doing so, it should think about working with the other states and the Federal Government on a wholesale review of their role in the property market, perhaps with a working group visiting Singapore (who doesn’t love a Junket?) to understand what is working there.

Of course, one of the biggest incentives for people to buy property is to make money, or at least to avoid being left behind. Whatever system replaces the various governments’ current involvement, it will need to consider this aspect (which Singapore seems to have preserved) while satisfying the other reason people buy; to provide security for themselves and their family, and a roof over their heads.

A working paper on Singapore’s housing system can be found here.