Investor Insights

SHARE

Is forecasting a waste of time?

I have had my fair share of bad calls. After more than three decades of investing, it’s safe for me to predict that there is next to no advantage in making predictions. What does make sense is to invest in great businesses and great managers and allow enough time to pass to allow the process of wealth creation within these businesses to occur.

That, of course, won’t stop the business of forecasting. I remember once reading that to forecast accurately, all one must do is…forecast often! You’ll eventually get one right.

Even a stopped clock is right twice a day.

Warren Buffett wryly observed that forecasts usually tell us more about the forecaster than the forecast. He has also opined, “We’ve long felt that the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good.” And perhaps even more wryly, Yogi Berra famously observed, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

This week I was asked to comment on a U.S. economist predicting a 40 per cent correction in the S&P500. Not wanting to comment without any background, I took to heart Morgan Housel’s famous suggestion to “Read last year’s market predictions, and you’ll never again take this year’s predictions seriously.”

Will that again prove to be the case?

The point of this post is not to sully anyone’s name (so we won’t be mentioning it) but simply to provide investors with some perspective about the business of forecasting and warn you not to react to the veritable sea of forecasts by even the most learned prognosticators. Stick to your investment strategy, your portfolio rebalancing approach and your investment philosophy.

This week on a Youtube channel hosted by a highly regarded former journalist, the famed U.S. economist, who previously worked at the Federal Reserve and Merrill Lynch (as did I at the latter) and is variously described as a ‘market prophet’ and ‘national treasure’, is predicting a 30 per cent correction in the S&P500, a recession and a bursting of the commercial real estate bubble.

Let’s put the recession prediction to one side because just about everyone has an opinion on that subject, which has been otherwise extensively documented. We’ll also put the commercial real estate crash to the side because that is objectively observable and doesn’t require any omniscience.

The stock market crash of 30 per cent, however, is an interesting subject.

The forecaster offered the following prediction; “I’ve been of the opinion that stocks would decline about 30 to 40 per cent, peak to trough. You’d have a further decline of about 30 per cent from here to get to that 40 per cent overall decline.”

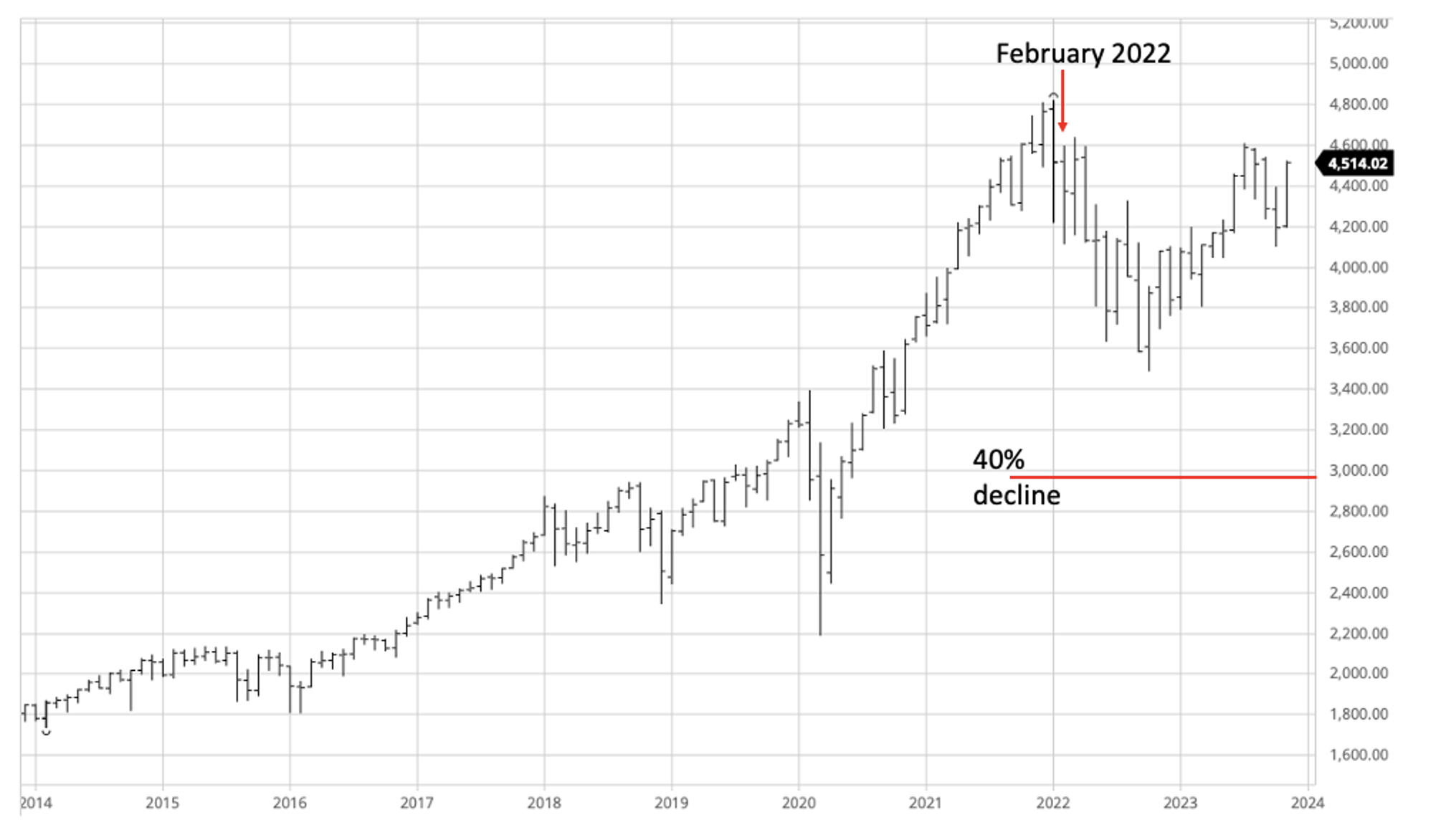

Figure 1. S&P500 Chart (monthly bars)

To many investors, hearing such a prediction, especially when it’s from someone with clear financial market bona fides, might give them cause to pause, to halt their investment strategy, or even to sell and go to cash.

But a little digging reveals the same forecast was made in February 2023. Back on February 1, 2023, the economist and forecaster observed, “The S&P 500 index is down 15 per cent from its early-2022 top as rising interest rates hammered stock valuations. The bulk of the decline, we believe, will occur this year as the unfolding recession decimates corporate earnings.”

In fact, at the time of that early February 2023 prediction, the index was 20 per cent below its February 2022 high, and the economist was predicting another leg down such that the total decline would amount to 40 per cent.

At the time of writing, however, and after 11 months have nearly elapsed, the S&P500 has not declined further but rallied 17 per cent from 3853 on February 1, 2023, to 20 November’s 4514 points.

At this point, it is worth noting that the predictions do not distinguish between the S&P500 and its constituents. As many readers would be acutely aware, about 30 per cent of the S&P500 index’s weight comprises just seven companies – Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, Nvidia and Tesla. In aggregate, these seven stocks have risen by 71 per cent year to date, according to Goldman Sachs. The remaining 493 stocks in the S&P500 have not performed, in aggregate, so spectacularly. In fact, five of 11 sectors are in the red this year, and without the magnificent seven, so would the S&P500.

So, investors are left to guess whether the economist’s forecasts and their linking of S&P500 predictions to economic conditions, such as employment and inflation, are a prophecy about the magnificent seven or the rest of the market.

Perhaps even more interesting is that the exact same prediction of a 40 per cent decline was made by the economist a year earlier, in February 2022. After that prediction was made, the S&P500 did, in fact, fall. That year the S&P500 declined 22 per cent by October 2022.

One begins to reflect on the observation that a stopped clock is correct twice a day, and to be an accurate forecaster, one merely needs to forecast often.

Back in 2010, the famed forecaster was also busy making predictions. Back in November 2010, they authored a book noting that we need to worry about deflationary expectations as growth will be significantly hindered. With consumers predicted to spend less, purchase generic items, and put behind them brand-name goods, producers will be forced to cut costs and margins. The economist added that investors may not see the glories of the 1980s and 1990s again.

As we all know, thanks in no small part to central bank largesse, the years 2010 to 2019 saw some of the fastest growth and wealth accumulation ever. With respect to the brand-name goods prediction, luxury goods behemoth Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH) grew its revenue from €18 billion in 2009 to more than €50 billion in 2019, before the pandemic hit.

Back in 2010, in the same book, the economist advised readers to avoid broad exposure to stocks, real estate, and commodities. It predicted deflation, a period of deleveraging and that stocks would grow slowly as nominal GDP experienced weak growth.

But by February 2020, right before the pandemic hit, the S&P500 index had fully tripled its level of the end of 2009. Household and non-household debt had soared, and inflation remained positive albeit low throughout, helping to fuel one of the most spectacular multi-asset bubbles in history.

I will continue to be asked about my expectations for the year ahead and whether it will be a good one for investors, but always remember the answer is an opinion rather than a forecast. There are only a few times in one’s life that the road ahead is blindingly clear. The rest of the time, it’s just noise. After three decades, I have learned that forecasts are less a prediction of the future and more a symptom of the past. They are a function of the environment in which they were made rather than a reliable guide to the future.