Investor Insights

SHARE

Qantas' past, present, and uncertain future: A CEO' departure raises questions

“I leave knowing that the airline is fundamentally strong and has a bright future,” are today’s parting words from Mr. Alan Joyce, now ‘former’ Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Qantas (ASX:QAN) and pictured below with Australia’s current Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese.

Source: NCA Newswire

There are many questions remaining, given the extraordinary reports about the behaviour of the airline towards its staff, customers and competitors. There are the more salacious ones related to whether Joyce fronted the board prior to retiring. Had the board set up a firing squad in readiness for a meeting with their CEO? Does retiring early without fronting the board – if that is what transpired – leave the board hanging out to dry, unable to demonstrate they took any action that recent events and reports suggest may have been required?

We’ll leave the answering of those questions to others. The more important question is whether the Qantas chairman and his board allowed short-term profitability goals – those that coincide with the CEO’s departure – to supplant the long-term reputation and value creation of the airline. And within a capitalist framework overseen by a policy of full disclosure does this even matter?

These questions should be at the heart of all forthcoming investigations and self-reflection. Shareholders are entitled to a CEO that maximises profit, but given they may remain owners of the business long after the CEO departs, are they entitled to know if the CEO and the board maximised short-term profits at the expense of their future? Did Qantas, its CEO or its board do this? And does it matter? Is it permissible?

In recent days, questions have begun surfacing about the board’s role in permitting and or approving Qantas’ monopolistic leveraging of its privileged status as a ‘national’ carrier. What was their role in the decision to block Qatar from 28 additional weekly slots that would have brought down the price of airfares for many Australians? Where were they when PM Anthony Albanese’s 23-year-old son was allegedly granted VIP membership of the privileged Qantas Chairman’s lounge? What discussions were had about returning any of the taxpayers’ $2.7 billion extended to Qantas in support during the pandemic? What is their role in daily management decisions such as the decision to cut back domestic capacity to make up for higher fuel costs, hitting consumers with a double whammy on fuel and airfares? And what was their response when, as has been reported elsewhere, Minister for Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development of Australia, Catherine King refused additional funding for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) Chair, Gina Cass-Gottlieb, to monitor and report on the domestic airline industry’s behaviour given “a lack of effective competition… [that] has resulted in higher airfares and poorer service”?

Clearly, it’s not just Qantas’ reputation that is damaged. The Australian Labor Parties’ (ALP) pattern of reported backroom deals and favours for mates at the expense of democracy and fairness is writ large. It must sully any reputation for integrity they might have had.

The names of Qantas’ board members began appearing more frequently in the press in recent days in the context of questions about their role and responsibility in this saga, no doubt pressuring them to act. The reported early retirement of the CEO may have undermined that demonstration.

You can find the Qantas board members here. They are Richard Goyder, Alan Joyce, Maxine Brenner, Jacqueline Hey, Belinda Hutchinson, Michael L’Estrange, Todd Sampson, Antony Tyler and Doug Parker.

When I look at the board of any corporation, I am often reminded of Richard Puntillo, Professor Emeritus at the University of San Francisco (USFCA), who some years ago was quoted thus: “in theory, publicly traded corporations have shareholders as their kings, boards of directors as the sword-wielding knights who protect the shareholders and managers as the vassals who carry out orders. In practice, in the past decade, managers have become kings who lavish gold upon themselves, boards of directors have become fawning courtiers who take coin in return for an uncritical yes-man function and shareholders have become peasants whose property may be seized at management’s whim.“

But the question today is whether the airline is 1) fundamentally strong, and 2) with a bright future.

Table 1., is taken from the annual reports of Qantas between 2008 and 2023 – the period corresponding to the most recent CEO’s tenure.

Table 1. The economics of Qantas

Source: Qantas Annual Reports

Tracking changes in equity, debt, profits, and dividends over a long period of time helps to understand the economics of an entity. In this case, it confirms airlines are tough businesses with generally mediocre economics.

Using statutory after-tax profit as contemporaneously reported by the airline for consistency, we can see that total net profits over the period – admittedly covering the COVID pandemic, which shut air travel down for an extended period – amounted to a loss of $116 million. In other words, no money was made on a net basis over the last 15 years. Clearly, that result can, in no small part, but in part, be blamed on the pandemic.

Interestingly, despite this loss over 15 years, the company evidently spent $2.226 billion buying back shares and another $1.659 billion on dividends. How, if it made a loss, did it fund $3.88 billion in dividends and buybacks? The answer may lie in the changes in debt. It could be that an increase in borrowings funded those buybacks and dividends. Comparing the balances at 2008 and 2023, short-term debt was $212 million higher, and long-term debt was $797 million higher at the end of the period. The total increase in debt of just over $1 billion might partly explain how the buybacks and dividends could have been funded. But there is still a ‘shortfall’ of $2.8 billion.

Perhaps only coincidentally, it has been reported that Qantas received $2.7 billion of taxpayer funds from the government during the pandemic. Putting aside the argument the government should have taken equity in the airline or extended the funds on commercial loan terms, the funds coincidentally amount to about what is required to have funded the buybacks and dividends otherwise unfunded by the increase in debt. Those curiously similar amounts might alternatively have helped shore up the balance sheet and cash flows of the business to the extent that the company was able to reduce long-term debt by a billion dollars in 2023 and buy back a billion dollars worth of stock in the same year.

And remember those economics described above are presented after allowing the airline’s fleet of aircraft to age. In other words, if the airline had purchased aircraft such that the fleet hadn’t aged, the numbers would have been worse.

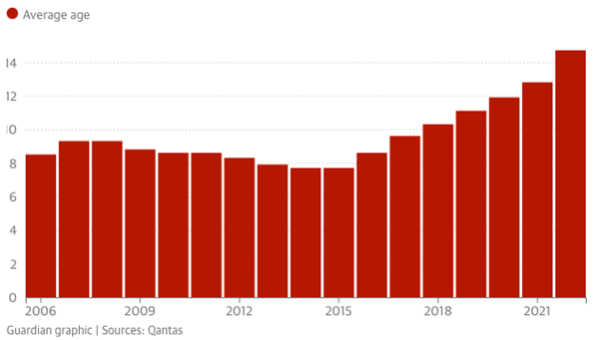

According to an article written in April this year by Nabeel Shaikh, on the simplyfly.com website, “The average age of a plane in Qantas’ fleet is 15 years – the highest of any major international airline in Australia. For reference, the average age of a plane is around the 10-year mark for aircraft belonging to competitors like Cathay Pacific, Emirates, and Qatar Airways.”

According to an October 2022 article in The Guardian, “In 2006, the average age of aircraft in the national carrier’s fleet was just eight years, but delayed purchases mean the fleet is now older than its competitors” adding, “and before the pandemic it was just over 11 years.”

Figure 1. Qantas average fleet over time

Figure 1., shows the average age of the Qantas fleet as reported by the airline. According to The Guardian, quoting Dr. Ian Douglas from the University of New South Wales, “So [fleet age] has almost certainly increased over time. And that would have been a conscious decision about managing capital by the board.”

It is worth noting that while the fleet has aged, many planes have done fewer ‘cycles’ (takeoffs, landings cabin pressurisations etc) because they were mothballed and grounded for years during and post the pandemic. Nevertheless, as can be seen in Figure 1., the path of fleet aging commenced well before the pandemic began.

And so, given Dr. Ian Douglas’ observation, we return to the most serious question that should now be asked about the extent to which the board participated in an apparent prioritisation of short-term profits over long-term reputation and, therefore, the value of the airline. Additionally, should anyone be held responsible for allowing a picture of profitability to be painted that might not reflect the true economics of the airline, if indeed that is what is discovered? Were any shareholders lured into purchasing shares in an airline that might, over the next few years – if it is going to reduce its fleet age to pre-pandemic levels – produce economics that could be much worse than even the modest economics displayed over the last fifteen years?

Is Qantas fundamentally strong? Does it have a bright future? The story is far from over, and much more ink will be consumed writing about it. Like you, as an Australian traveller, consumer and citizen, we look on with great interest and await the answers to these important questions.