Investor Insights

SHARE

The U.S. Healthcare Quandary

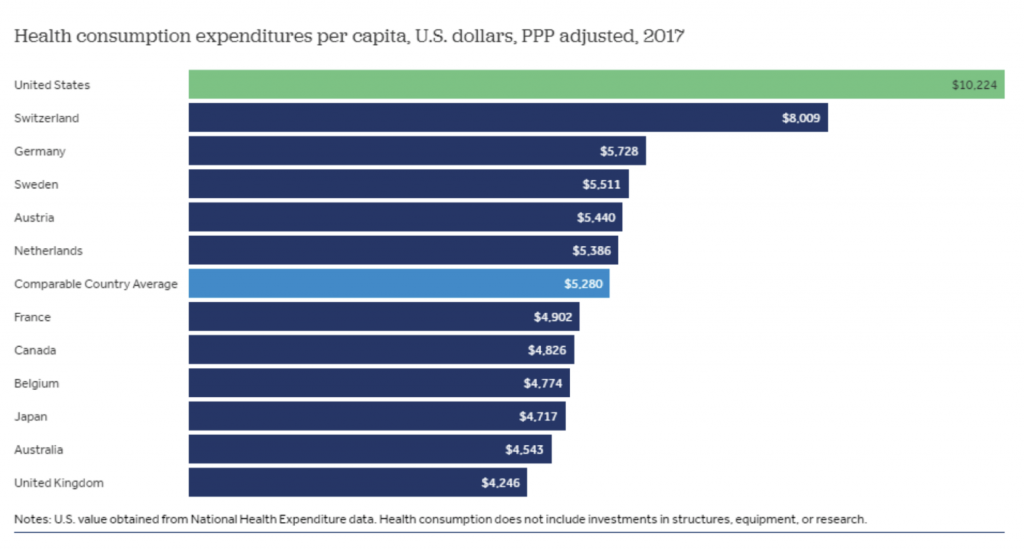

While many lament the sad state of the U.S. healthcare system, with U.S. healthcare expenditure being multiples of other developed nations on a per capita basis, attempts to reign in this inflating healthcare expenditure have been ineffective, with the gap widening between U.S. healthcare spending and that of other comparable countries. However, there are a number of proposals on the horizon that could drastically impact U.S. healthcare expenditure and the various firms in the healthcare value chain.

In 2018, the U.S. spent $3.5 trillion, or $10,739 per person, on healthcare, equating to approximately 18 percent of GDP. The 2017 figures below, which are PPP adjusted, show just how far ahead the U.S. is in per capita expenditures on healthcare compared to other developed countries.

Source: Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker

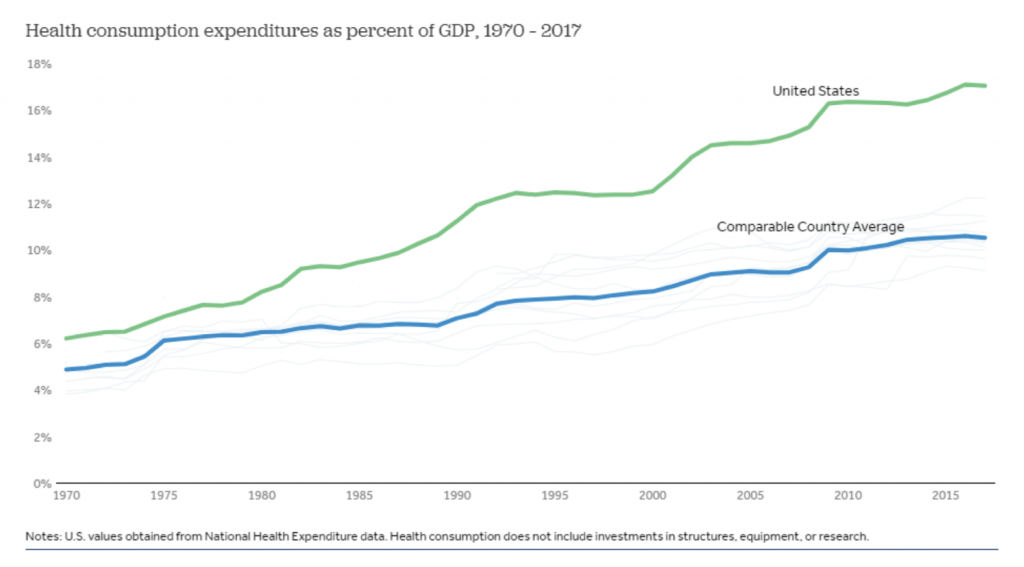

While the dynamic of U.S. healthcare expenditure being greater than other developed countries is not a new one, the spending gap has widened in recent decades. In 1970 the U.S. spent around 6 per cent of its GDP on healthcare, compared to 5 per cent for other wealthy countries in the same year. However, the U.S. now spends around 18 per cent of its GDP on healthcare, with the next highest comparable country, Switzerland, spending 12 per cent of its GDP on healthcare.

In late 2018 the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed the Medicare Part B IPI via what is known as an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM). The ANPRM document sets out what the IPI Model seeks to achieve: “The IPI Model aims to drive better quality for Medicare beneficiaries and reduce Medicare drug spending by offering comparable pricing relative to other countries and addressing flawed incentives in the current payment system.” In other words, the IPI Model applies to a subset of physician-administered drugs under the Medicare Part B program, and aims to cap U.S. drug acquisition costs based on prices paid in an index of developed nations.

How significant will the impact of this IPI Model be in reducing the prices paid for U.S. drugs? This depends on the magnitude of the difference in the cost of drugs between the U.S. and comparable countries, and an analysis undertaken by HHS suggests that this difference is material. The HHS study looked at drug acquisition costs for a set of Medicare part B physician-administered drugs for the U.S. compared to 16 other developed countries. Looking at 27 products in the analysis, the drug acquisition costs in the U.S. were found to be 1.8 times higher than in developed peer nations, with the cost ratios ranging from on par, to prices in the U.S. being 7 times greater than those paid offshore.

A number of years ago in a Twitter exchange, Steve Miller, the Chief Medical Officer at Express Scripts, summed up the issue faced by the U.S.: “The U.S. is 4.6 percent of the world’s population, we’re 32 per cent of the world’s drug revenue, and we’re somewhere between 50 and 70 percent of world drug profitability”. In effect, the U.S. is subsidising the drug costs of other nations, acting as a profit centre for pharmaceutical companies to fund their R&D expenditures. This dynamic is unsustainable, and with bipartisan support to tackle this issue, as well as an administration willing to enact transformative policies, it’s likely that the healthcare industry could see substantial change over the next few years.

Healthcare costs are a top-of-mind issue for U.S. voters going into the election late next year. If the IPI Model were to be put into action, there are likely to be significant impacts to the various players in the healthcare value chain, and the Montaka team continues to monitor changes in the healthcare landscape in order to identify opportunities on both the long and short side.