Investor Insights

SHARE

War. What is it good for? Well, surprisingly, equities

Edwin Starr’s classic 1969 anti-war song, War, asks: “War: What is it good for?” and responds emphatically “absolutely nothing.” It’s hard to argue with the sentiment. But it turns out Starr was not completely correct. You see, despite the terrifying carnage and destruction, war can often be a fruitful time to invest.

Let me be clear: I detest armed conflict. War should be avoided at all times and not prompted by immature despots, seeking acclaim they can only take to their grave.

With Russia and the Ukraine on the brink of war, and with markets predictably reacting negatively, I thought it is worth revisiting the enquiries I made the last time an armed conflict threatened to destabilise the world and markets.

History suggests past conflicts have not inflicted permanent pain on investors. It has indeed been wise, historically, to invest at the depths of the conflict when fear was at its extreme.

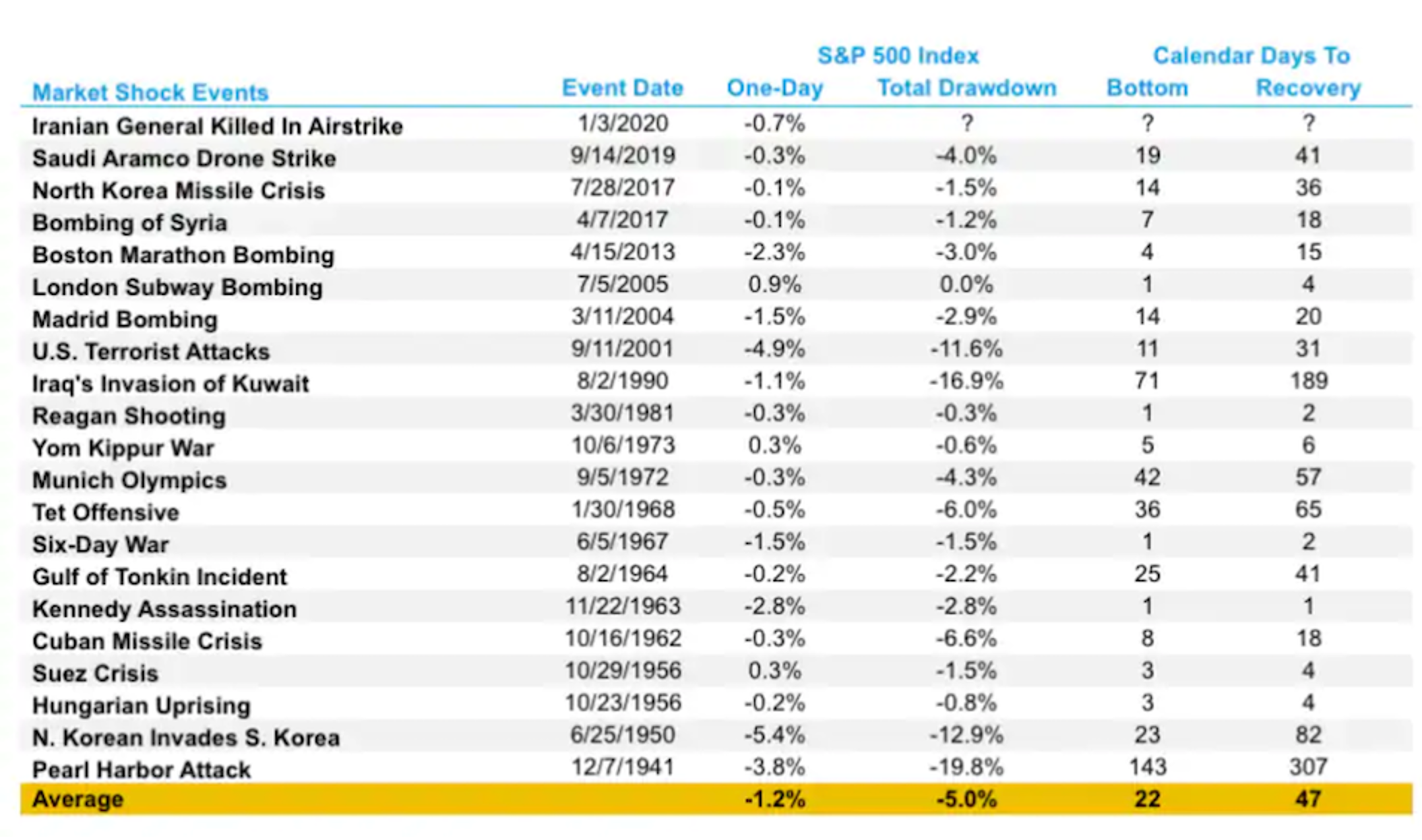

Research by LPL Financial, conducted in 2020, of market reactions to past geopolitical crises confirms stock market investors have mostly shrugged off geopolitical conflicts as some sectors and companies have continued to generate profits.

Of course, that latter observation doesn’t let investors off the hook because stocks can, and frequently do, move independently of the performance of the underlying business.

Table 1, from 2020 by LPL Financial reveals however investors would be wise not to sell into the fear and weakness but instead, remember that there have been dozens, if not hundreds, of conflicts in the past and the stock market has survived. This of course is not to diminish the very real suffering at the hands of tyrants and dictators, which democratic allies should pull all stops to prevent.

Table 1. A summary of geopolitical events and stock market reactions

Source: LPL Research, S&P Dow Jones Index, CFRA. 1/6/20

Let’s put the current invasion of Eastern Ukraine by Russia into some perspective.

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Dow Jones declined almost a third within six months. Business ground to a halt and liquidity in the stock market vaporised as foreign investors sold US stocks to raise money for the war effort. The NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) closed on July 31, 1914. The world’s financial markets closed their doors by August 1. The NYSE was closed for four months. It was the longest suspension of trading, and circuit breaker, in history. Almost immediately, however, a substitute trading forum called the New Street market emerged and trading began offering economically meaningful liquidity but impaired price transparency.

Closing the stock exchange for a third of a year would be unthinkable today. It was unthinkable then. To wit: “If at any time up to July, 1914, any Wall Street man had asserted that the stock exchange could be kept closed continually for four and one-half months he would have been laughed to scorn.”[1]

It must have seemed grim for stock market investors, especially for anyone with capital tied up and locked down.

After the stock market reopened in 1915, however, the Dow Jones rose more than 88 per cent. 1915 recorded the highest annual return on record for the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

From the start of World War I in 1914, until its end in 1918, the Dow Jones rose 43 per cent or about 8.7 per cent annually.

The Second World War must have seemed primed to be a whole lot worse.

From the start of WWII in September 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland, until it ended in late 1945, the Dow Jones rose 50 per cent – equivalent to a compounded seven per cent per annum.

In other words, the two most damaging conflicts in history saw the stock market rise meaningfully.

On 7 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, by surprise, stocks opened the following Monday down 2.9 per cent, but it took just a month to regain those losses. And then, when the allied forces invaded France on D-Day on June 6, 1944, the Dow Jones barely reacted and rose more than five per cent over the subsequent month.

Caveat(s)

According to research conducted in 2015, into U.S. military conflicts after World War II by the Swiss Finance Institute, stock prices tend to decline in the pre-war phase and recover when war commences. But when war is a complete surprise, stocks decline.

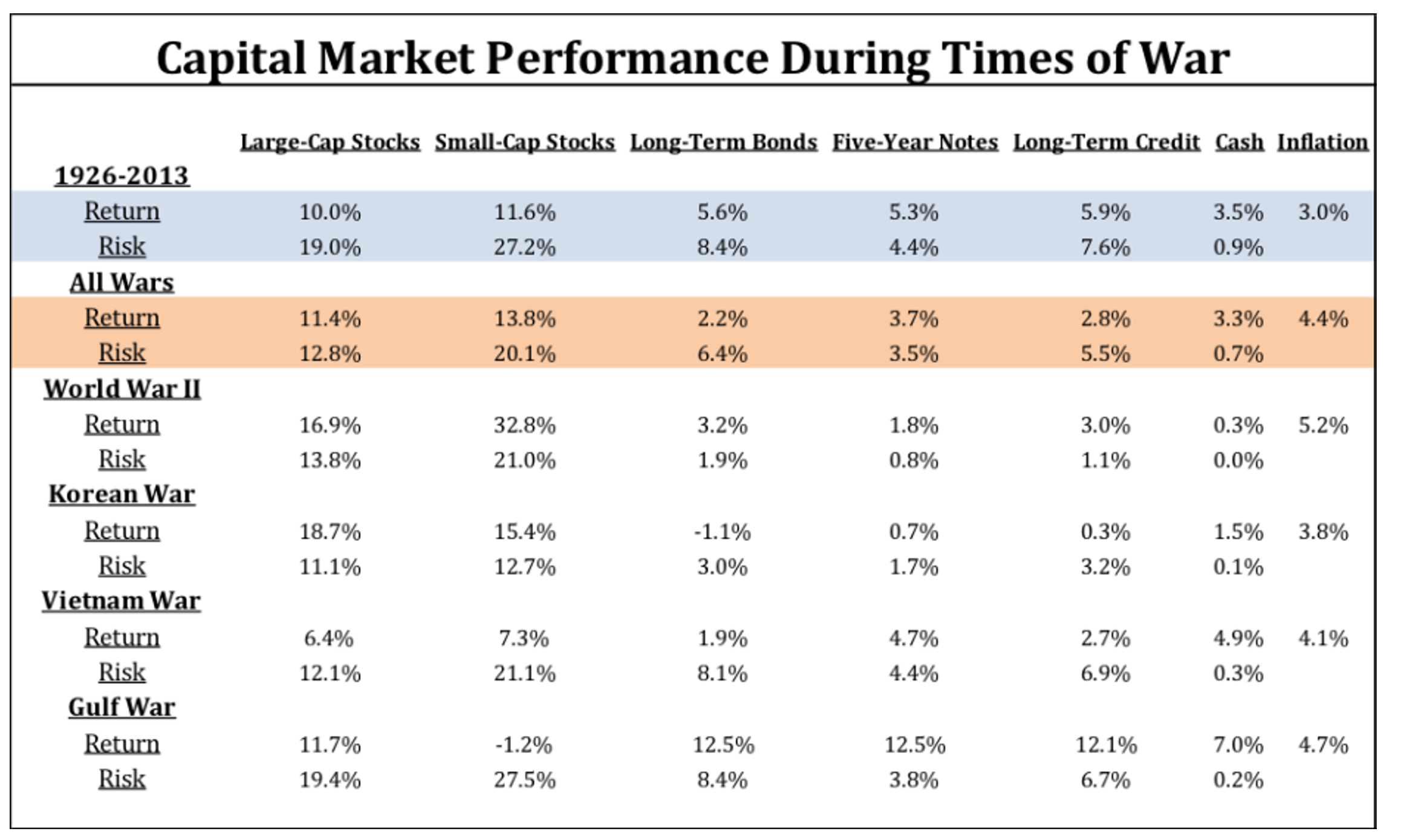

Another study, published in 2013 by Mark Armbruster, of Armbruster Capital Management, examined the period from 1926 through July 2013 and found that stock market volatility was actually lower during periods of war.

“We looked at returns and volatility leading up to and during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War. We opted to exclude the Iraq War from this group, as the Iraq War included a major economic boom, and subsequent bust, that had very little do with the nation’s involvement in a war.

“As the table below [Table 2.] shows, war does not necessarily imply lackluster returns for Domestic stocks. Quite the contrary, stocks have outperformed their long-term averages during wars. On the other hand, bonds, usually a safe harbor during tumultuous times, have performed below their historic averages during periods of war.”

Table 2. Capital market performance at times of war

Source: Mark Armbruster/CFA Institute

In recent years, the 9/11 attacks and the Global Financial Crisis in particular, have trained investors to expect central banks to rescue them through the repression of financial market volatility. Moreover, the belief and hope the initial conflict doesn’t escalate, drawing in the rest of the world, has also been supported by real world experience.

Investors have thus been conditioned to eschew an overreaction.

It is probably the fear of an all-inclusive war that inspires investor reaction to even the most minor of conflicts involving powerful nations but investors do well more often than not, when they remain invested, take advantage of weak prices and correctly bet that sober hearts and minds will prevail.

Most of the time it is economic and idiosyncratic fundamental factors that impact security prices. Very rarely, a solitary exogenous event is influential enough to override the usual factors and impact market returns materially.

Based on research of history and the above data, however, war and geopolitical conflicts shouldn’t be counted in that category.

[1] Noble (1915, p. 87).