Investor Insights

SHARE

What is our “variant perception” to the market?

First, it was Warren Buffett not buying stocks and, indeed, liquidating large portions of his portfolio to build cash. Then, last week, we had Stanley Druckenmiller tell The Economic Club of New York that “the risk-reward for equity is maybe as bad as I’ve seen it in my career.” As equity markets continue to rise, investors are slowly getting nervous about the upside potential from current levels over the short and medium terms.

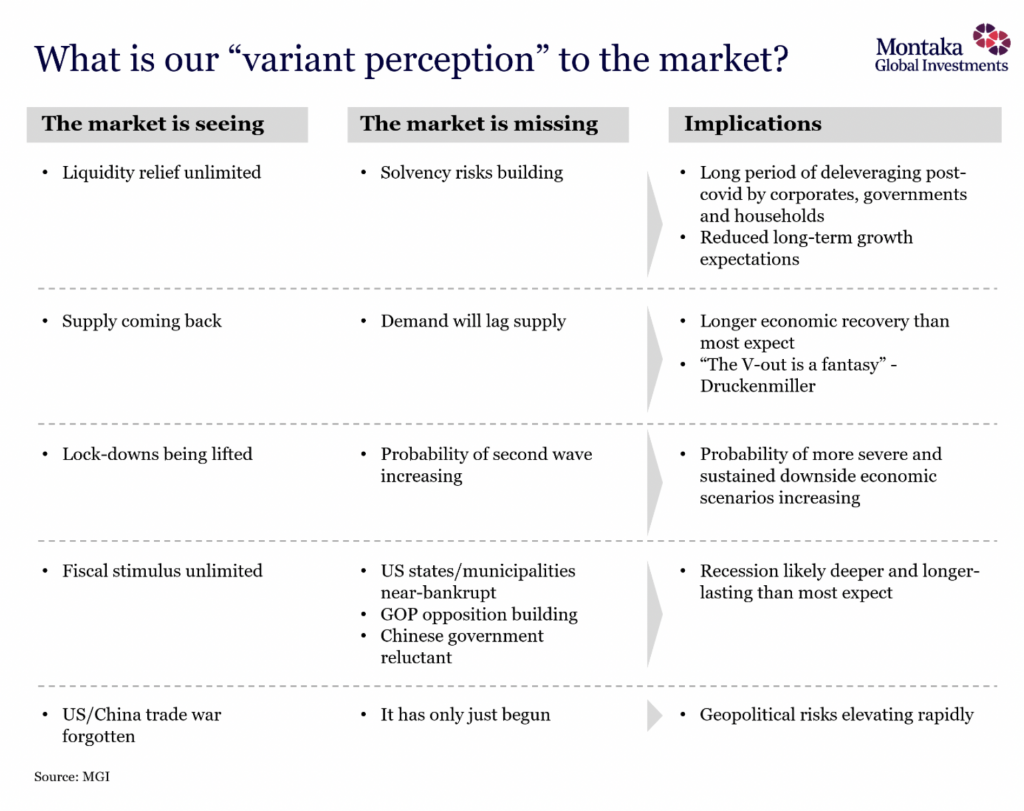

As they should be, in our view. Across at least five dimensions, we can isolate sources of great optimism being focused on by equity markets – as well as instances of wilful blindness that result in the downside risks being identified by the likes of Druckenmiller, David Tepper and others. These collectively represent our “variant perception” to the market today.

First, the market has clearly reflected the enormous liquidity injection into the monetary system from the Fed and other major central banks. This ensures that new and existing borrowings can be refinanced. But what about the build-up of solvency risks? Ultimately these borrowings have a more senior claim on a company’s assets and cash flows than the claim owned by shareholders. Coming out of this crisis will be a long period of deleveraging by corporates, households and governments. And this will likely reduce longer-term economic growth.

Second, the market is clearly observing supply coming back – which is great. Shops are opening, factories are opening and people are going back to work. But what is even more important is demand coming back. And the evidence out of China and Europe so far is that this is lagging. The COVID-19 shock has driven significant unemployment and likely increased the risk aversion of most households. We believe this shock has pushed up the propensity for households to save; and pushed down the propensity for households to consume.

Third, the market has rallied on societies lifting their lock-downs. While this is the first step to economies opening back up, something we all hope will happen quickly, it also significantly increases the probability of a second wave of COVID-19 infections. A second wave would be disastrous for the global economy with respect to both the severity and duration of the current recession.

Fourth, the market has applauded the very strong fiscal stimulus measures being effected by governments all over the world. We believe the market is effectively pricing in an unlimited amount of fiscal stimulus to offset any and all COVID-19 recession related shortfalls in demand that may play out. But we are seeing indications that government stimulus may actually fall short of what is required. In the US, many states and municipalities are essentially bankrupt today and will need significant federal government support. They represent a negative fiscal stimulus contribution. Meanwhile, Republican party support for more fiscal stimulus is waning. And in China, the government is reluctant to commence another debt-fuelled stimulus that would set back years of deleveraging efforts.

Finally, we believe the market is overlooking the deterioration in the relationship between the US and China. After the Phase I trade deal that was signed last year, the market may believe the trade dispute is a thing of the past. The reality is that it has only just begun. And in recent weeks, as many countries become frustrated with China’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak, we observe that China’s bilateral relationships are growing increasingly more strained and contentious by the day. And this raises risks for the entire world.

We see downside risks in equity markets near-term. For markets to remain elevated, the economy needs to rapidly bounce back, we need to see no material resurgence in COIVD-19 cases, China needs to remain friendly with its major trading partners and government stimulus needs to remain abundant. It is true that all of these things could happen. But we place a higher probability on a scenario playing out in which they don’t.