Investor Insights

SHARE

Would you like some sugar with your mortgage?

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) latest rate rise has serious consequences for consumers and investors. There can be no argument that the RBA’s battle against inflation dominates investment commentary.

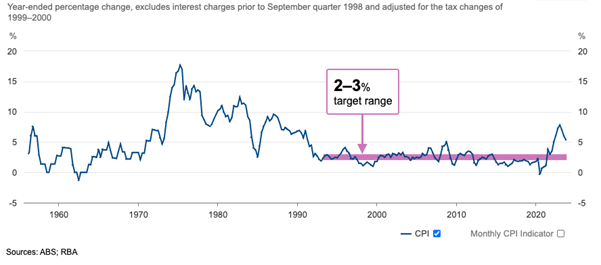

Figure 1. Australian annual inflation

And even though inflation is cooling in Australia, food price increases remain steep.

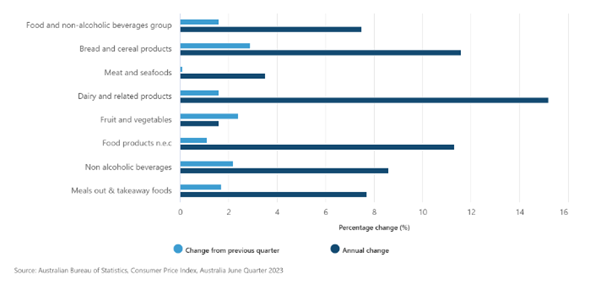

Figure 2. Australian food components of inflation, June quarter 2023

While dairy leads the price rises, breads and cereals are increasing annually by more than 11 per cent. And because these increases reflect what consumers pay at the checkout, the falling overall inflation rate masks the larger share of wallet required for spending on necessities. And that means less at discretionary retailers and other businesses, suggesting analysts may need to revise their earnings growth predictions and delay the hitherto widely anticipated recoveries.

To help explain why your foodstuffs are rising in price, look no further than one of their most common ingredients sugar. U.S. sugar futures are trading at prices that have only been reached during three episodes in the last 50 years.

The March 2024 Sugar#11 futures contract, the world benchmark contract for raw sugar trading, closed at the time of writing at U.S.27.59c/lb. The sugar price has only been this high in 1974-1975, 1980-1981 and 2010-2011.

Figure 3. Sugar #11 futures front-month contract to 7 November 2023

That makes current sugar prices historically significant. For Australian equity investors, an understanding of the influences on sugar prices may go some way to determining whether its contribution to inflation is likely to persist.

History

New Orleans-born Norbert Rillieux (1806-1894) revolutionised sugar processing with the invention of the Multiple Effect Evaporator under Vacuum. “Rillieux’s great scientific achievement was his recognition that at reduced pressure, the repeated use of latent heat would result in the production of better-quality sugar at lower cost.”

His efforts effectively commoditised sugar from what had hitherto been a luxury item. It also rendered the U.S. a global leader in sugar production.

Around the same time – in the late 1870s – Dr. John Harvey Kellogg created a granola as part of his health regimen for his Battle Creek Sanitarium patients. Then in August 1894 Kellogg discovered that forcing stale wheat dough through rollers, turned the dough into flakes that could be toasted and eaten after being soaked in milk before serving. And corn worked even better. In 1894 Kellogg created Corn Flakes, and the modern union of sugar and starch was born. By 1896 he had secured a patent for flaking cereals.

In 1914, sugar futures began trading in the U.S. on the coffee, sugar and cocoa exchange in New York and the New York Board of Trade.

Today

Breakfast cereals contain high levels of sugar, especially in the U.S. meanwhile, at 33 per cent, according to the U.S. economic census, the cost contribution of sugar is the highest, compared to all foods, for breakfast cereals. The cost share of sugar as a raw material in breakfast cereal manufacturing is almost 33 per cent, which places it above confectionery products including non-chocolate and chocolate, ice cream, frozen desserts and soft drinks.

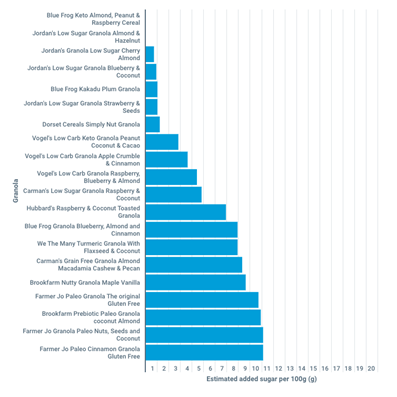

By way of example, a 39 gram (1 1/3 cups) of Kellogg’s Fruit Loops contains 12 grams of sugar (30.1 per cent). Nutri-Grain is one-quarter sugar. Figure 4., reveals Australian granolas with the least amount of sugar.

Figure 4. Granolas with the least added sugar

Source: Choice

Healthier granolas however tend to be outsold by mass-produced sugar-filled cereals with packaging designed with cartoon characters to appeal to children.

In the U.S., brands like Honey Nut Cheerios from General Mills, sells more than 129 million boxes annually, and has 32.5 per cent sugar per serving. Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes sells approximately 132 million boxes a year and is also almost one third sugar. Meanwhile, Cap’n Crunch, Crunch Berries contains 43 per cent sugar by serving.

Of course, breakfast cereals are only one of many food types loaded with sugar. Others include baked bread and pastries, tomato and BBQ sauces, yoghurts, premade soups, protein bars, iced teas, sports drinks, and so on.

To supply all these foods with sugar, approximately 180 million tons of the stuff is produced annually. The largest exporter is Brazil, with more than 28 million tons exported in the 2022/23 marketing season. Most of Brazil’s production occurs in the nation’s center south.

Thailand and India are the next largest exporters, with a combined 17 to 18 million tons exported annually.

Importantly, in the current marketing season, India has limited its global exports to just 6.1 million tons, which is down 44 per cent from 11 million tons in the prior year.

And even more importantly, India is expected to ban the export of its sugar next marketing year.

This rising price of sugar is detrimental to the share prices of cereal manufacturers. Year-to date, Kellogg is down 24 per cent, while General Mills has declined 22 per cent.

The future

Perhaps counterintuitively, the detrimental impact of the rising price of sugar on these businesses could serve to bring sugar prices down. As India restricts its exports, keeping sugar prices elevated, businesses dependent on the ingredient must investigate alternative sweeteners, such as sugars from other plants, including palm, stevia, maple, and coconut. Alternatively, these brands create cereals that taste just as good with less sugar. And rising prices for popular cereals simultaneously force consumers to shop elsewhere or skip breakfast entirely and intermittently fast.

Who would have thought India’s sugar exports and whether Americans skip breakfast might influence your mortgage rate here in Australia! The link might seem tenuous but it’s there!