Investor Insights

SHARE

Zero forever?

Last Wednesday, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell issued an unequivocally dovish assessment of the US economy in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Following the Federal Open Market Committee’s decision to hold its overnight benchmark rate at zero, Powell expressed concern over the medium-term economic and employment outlook, and reiterated the Fed’s commitment to utilise its full range of tools to support the U.S. economy. To that end, Fed officials forecast no increase to the Fed Funds target rate through December 2022 and maintained the current pace of $120 billion Treasury and MBS purchases a month.

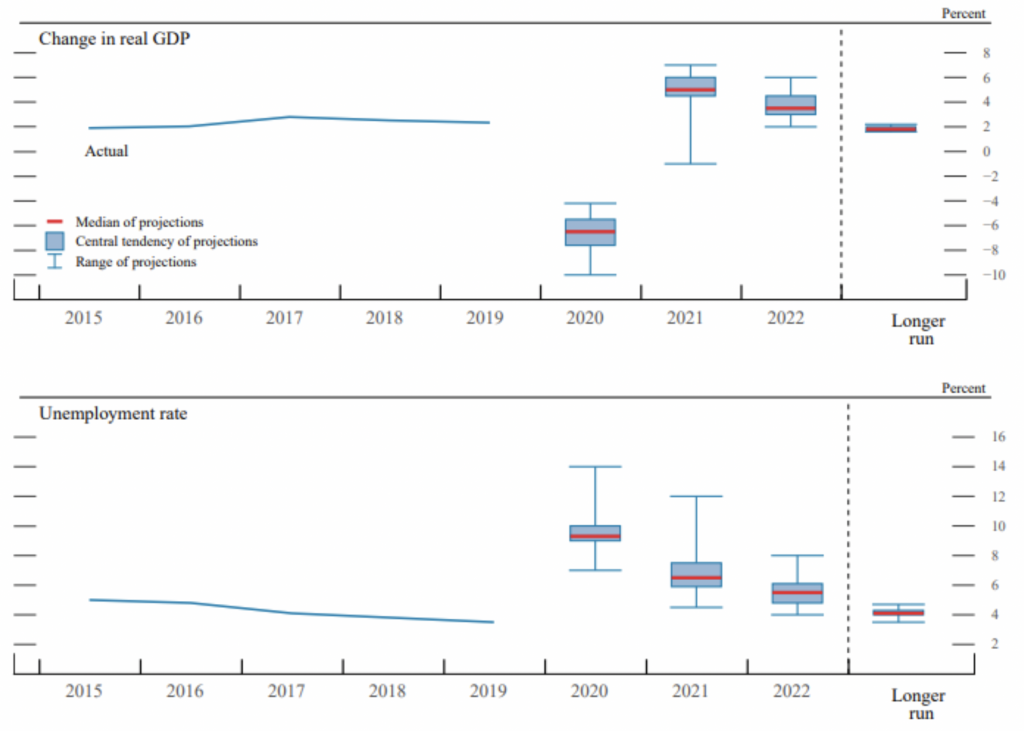

The FOMC statement and Powell’s press conference were clearly intended to bolster confidence in the Fed’s extremely accommodative policy stance (not even a hint of tightening as far as the eye can see), but in a surprising yet inevitable twist, investors finally took bad news to be bad news. Underlying the Fed’s expectations that rates remain at zero until the end of 2022 is the uncomfortable fact that none of the policymakers know what is going to happen. Officials expect 2020 GDP to decline between -4 per cent and -10 per cent and unemployment to be between 7 per cent and 14 per cent, while 2021 ranges are even wider. The equity market, which has ripped higher over the past several months in defiance of real-world economic realities, finally stumbled and tumbled 6 per cent on Thursday.

Source: FOMC Press Conference Projection Materials, June 10, 2020

What does the Fed’s zero-rate stance mean for equities and equity investors? For starters, expectations of zero interest rate until December 2022 may as well be forever given the typical short-sightedness of the market. We published a whitepaper titled “Low rates, assets inflate” discussing our views on a lower-for-longer rate environment back in December 2019 when the Fed Funds rate was still at 1.75 per cent, and our conclusions are even more applicable today. Any expectations that the Fed will eventually “normalize” rates or shrink its balance sheet must be tempered with market reality. When the Fed tried to tighten interest rates to a “normal” level in 2018 during a favourable economic environment, the market threw a tantrum and the Fed quickly reversed course. Likewise as the Fed continued to shrink its balance sheet in 2019, it almost broke the repo market and again had to pump liquidity back into the market. What this means is that investors positioning their portfolios for either of the above events will likely be disappointed even in the medium-to-long term.

Investors will inevitably need to accept a lower discount rate in order to participate meaningfully in equities. However, this does not mean investors should be piling into equities right now, especially with such a divergence between asset prices and economic reality. A lower discount rate equals objectively higher asset prices, but given the confluence of economic, geopolitical and social headwinds in the near and medium term, investors need to be highly selective about the stocks they buy. Now more so than ever is the time to own high quality compounders – those resilient to economic shocks with stable, predictable and growing cash flows – for the long term.