Investor Insights

SHARE

Exchanged Traded Products and Income: Same same but different?

Today, our markets are awash with ETFs, ETMFS, LICs and LITs. The beauty of these exchange traded products is that they offer investors instant diversification in a single trade. But they have some key differences. And it’s worth knowing what they are.

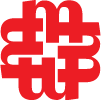

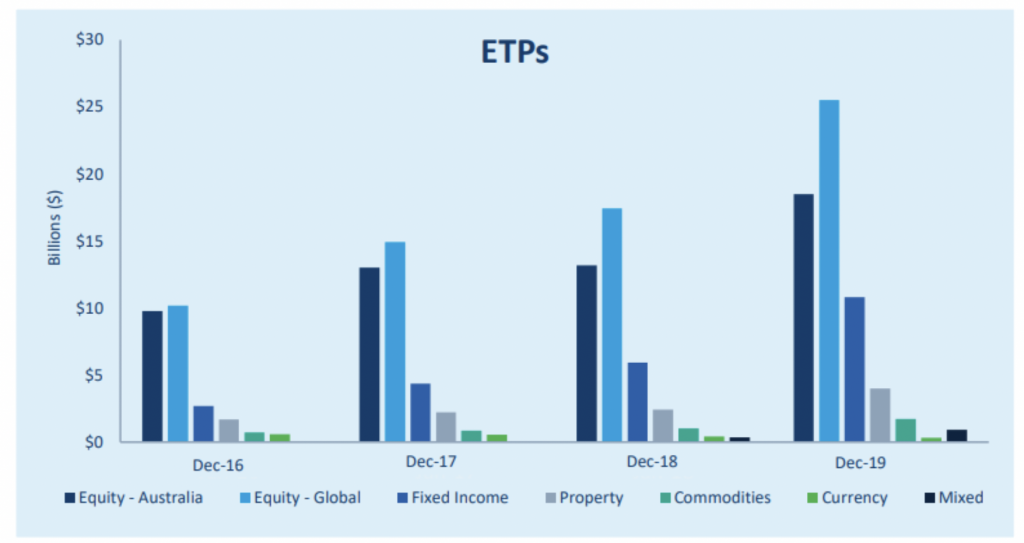

The first Exchange Traded Products (ETPs) listed on the ASX 19 years ago under the tickers ASX:SFY and ASX:STW. This was actually about eight years behind the US which had the first strategy of its kind come to market in 1993 under ticker NYSE:SPY. Over the last decade asset growth in this space, including Australia (albeit still lagging the US) has been very robust, with ETPs and their close relatives in Listed Investment Companies (LICs) and Listed Investment Trusts (LITs) closing calendar year 2019 at $114.66 billion by market capitalisation on the ASX, including 324 different strategies across multiple asset classes, investment styles (including active verse passive) and of course our very own Montgomery Global Equities Fund ASX:MOGL. This represented growth by market capitalisation of 52.2 per cent in ETPs over calendar year 2019, and 29.6 per cent in LICs/LITs. This is shown below in Graph 1 and 2 along with the last four calendar years and across a number of the major asset classes.

Graph 1 – Growth of ETPs on the ASX over four years across major asset classes

Graph 2 – Growth of LIC ’s & LIT’s on the ASX over four years across major asset classes

Source: ASX

I think it’s safe to say the ETP, LIT and LIC market is here to stay, and it’s recent growth can be attributed to every day investors and their demand for a greater variety of investment vehicles, whether it be across a number of geographies and/or asset classes, to be made accessible via the ASX via one simple trade. Of course, a number of these investors (and a growing number at that) are retirees who might be attracted to such listed investment vehicles that pay a consistent income, either in the form of a distribution yield or a dividend. Discussed below, I will look to explore how ETPs, LICs and LITs deal with income as it may have implications as to which investment vehicle might best suit your investment and income needs.

ETPs

ETPs broadly encompasses two different types of listed investment vehicles, being Exchanged Traded Funds (ETFs) and Exchange Traded Managed Funds (ETMFs). The common equation to both investment strategies is really the ‘F,’ meaning have both have the same structure as opened-ended, listed managed funds. Ipso facto, they operate from an income perspective in an identical fashion to an unlisted managed funds (like The Montgomery Fund or the Montgomery Global Fund), which we have written extensively about in the past here.

Putting structure aside, there is a difference between the two which can be defined by the ‘M,” meaning they both have management differences in that ETFs are generally rules based or passive investment strategies (such as the index tracking Vanguard International Shares ETF ASX: VGS), and ETMFs are generally actively managed investment strategies (which may aim to outperform an index, like our ASX: MOGL). These funds, like their unlisted equivalents, are required to pay (or distribute) at a minimum all net realised capital gains and income (less fees) within the fund, although some investment managers may choose to pay out more. Such payments often are annually, although some managers may also choose to distribute realised earnings six monthly, or even quarterly.

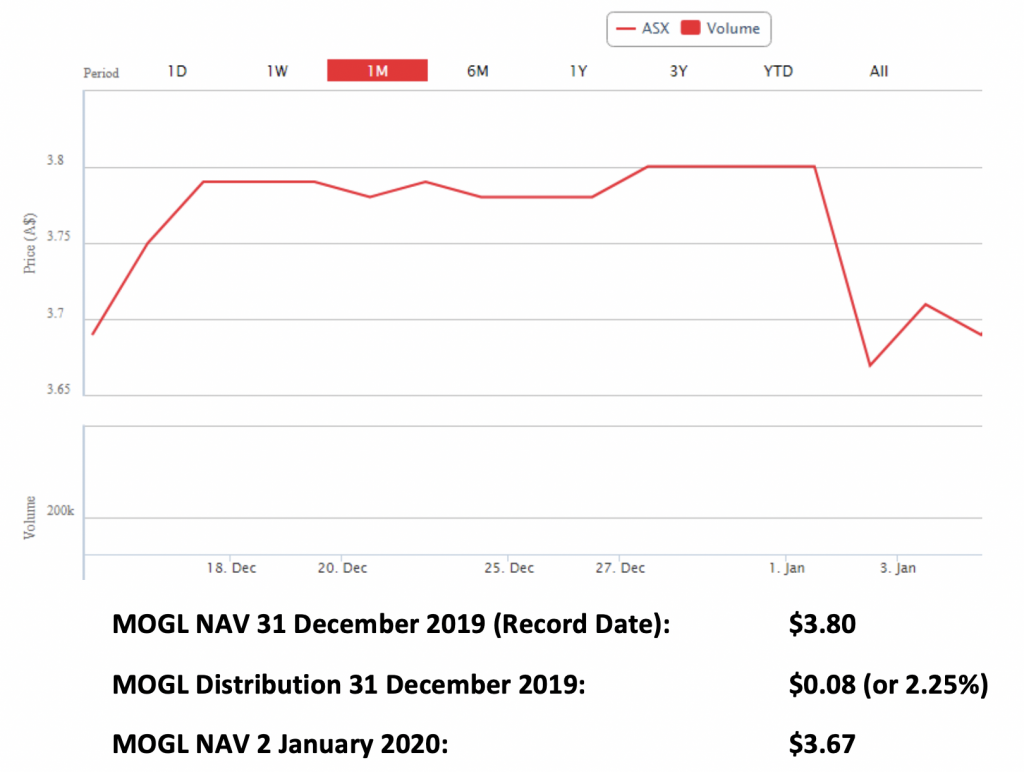

Such a payment is importantly referred to as a distribution yield as opposed to a dividend. The reason why it is not called a dividend is because the payment consists of all realised earnings, which can be dividends (both global and local, including potential franking credits) but also more broadly realised gains verse losses (from trading of the underlying assets) and any interest from cash bearing investments within the unit trust. Also like an unlisted managed fund, an ETF and ETMF will go ex-distribution when the distribution is paid, and the share price will move by the amount of the distribution plus (or minus) any market movement between the ex-date and next Net Asset Value (NAV) date. An example of this is as below in the case of ASX: MOGL, which targets a minimum distribution yield of 4.5 per cent per annum paid six monthly, although it can pay more than this (which it did on 30 June 2019). The distribution for the six months to 31 December was 8.37 cents per unit, representing a distribution yield of 2.25 per cent. Upon going ex-distribution, the share price fell by this amount plus some market movement from daily change in the value of the underlying portfolio of listed global equities between 30 December and the next NAV date, 02 January (given the public holiday and subsequent market closures globally on the 01 January).

Graph 3 – ASX: MOGL share price movement pre and post distribution 31 December 2019

Source: MGIM

LICs & LITs

Let’s start off with the similarities here with ETPs, firstly focussing on LICs. LICs like ETPs from a strategy perspective can invest in a portfolio of assets that are passively or active managed and are similarly traded on the ASX. Where they most differ with ETPs is twofold. One, they are a close-ended investment vehicle, and as such there is a fixed number of shares issued upon listing. This, therefore, means shares can only be bought when another shareholder is selling, when the LIC/investment manager raises capital (like any listed company), and when the LIC/investment manager buys-back shares (also like any listed company). Consequently unlike ETPs which are open-ended and have market maker(s – can be multiple) to ensure the Fund trades at a narrow spread to the NAV, LICs can trade at discounts or premiums as the share price is not only influenced by the value of the asset the LIC holds, but also by the supply and demand of the shares on issue. The investment manager can try to manage this through share buy-backs and capital raisings. Secondly, given the structure of an LIC is like that of any listed company but in this case whose primary business is simply running the underlying portfolio in accordance with their investment mandate, it’s realised earnings can be paid out in the form of a dividend (including potential franking credits) or can be retained as after tax profits within the company itself and as such not distributed. This is a key difference with ETPs which are required at a minimum to distribute all realised earnings, and such earnings retained in the LIC are taxed at the corporate rate. Furthermore, given the structure is that of a company they’re also not required to disclose holdings to the ASX in full which now applies to all ETPs. For example, ASX:MOGL discloses its portfolio in full to the ASX under such rules quarterly.

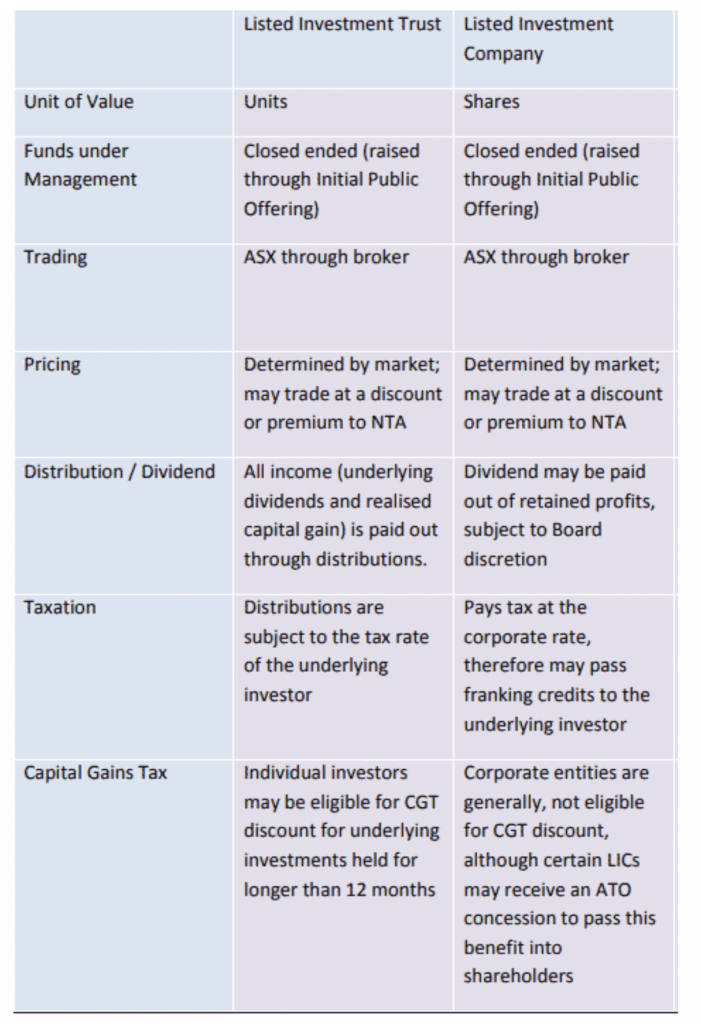

LITs, the newest of the listed investment vehicles, can be more closely likened to ETMFs in that they are (in the case of Australia) all actively managed and adopt the form of an investment trust, meaning they are required to distribute all realised earnings to shareholders in the form of a distribution yield. However, like their older sibling in LICs, they are close ended so have a fixed number of units upon listing and do not carry the same holdings disclosure requirements as ETPs. Some of these differences have been summarised in the table below.

Table 1 – Summary of key differences between LITs & LICs

Source: Morningstar

According to Rainmaker, the Australian ETP market is projected to grow to $600 billion in FUM by 2030. As such, income seeking investors on the ASX should not let the acronyms scare you away from understanding how these investment vehicles differ in their treatment of income. For those interested, you can also view the full current ASX ETP menu here.