Investor Insights

SHARE

Holding for the long-term

“Our favorite stock holding period is forever” Warren Buffett once mused. On the surface this might sound at odds with the adage of buy low and sell high, given the absence of any selling. It’s worth exploring what Buffett meant, and the circumstances in which it might make sense to follow this piece of advice.

Buffett’s quote might sound simple, but it embodies several important, and sometimes under appreciated, concepts. A holding period of forever only ever makes sense if a company is able to employ capital at high rates of return and grow its earnings power over time. The opposite of this – that is, a company with stagnant or declining earnings power – is the enemy of the long-term investor, as even a seemingly low-price tag might not be low enough if the earnings dwindle over time.

Charlie Munger once said “the first rule of compounding: Never interrupt it unnecessarily.” If one can find a high-quality business that can compound its earnings over time, a holding period of “forever” removes the temptation to sell and lock in short term profits, potentially forgoing a much larger investment profit over time. This might sound odd.

Why wouldn’t it make sense to capitalise on short term market volatility by buying low and selling high? Wouldn’t this amplify the compounding effect, by gaining from the earnings multiple arbitrage in addition to the longer-term growth in the company’s earnings? The answer is yes, but not reliably.

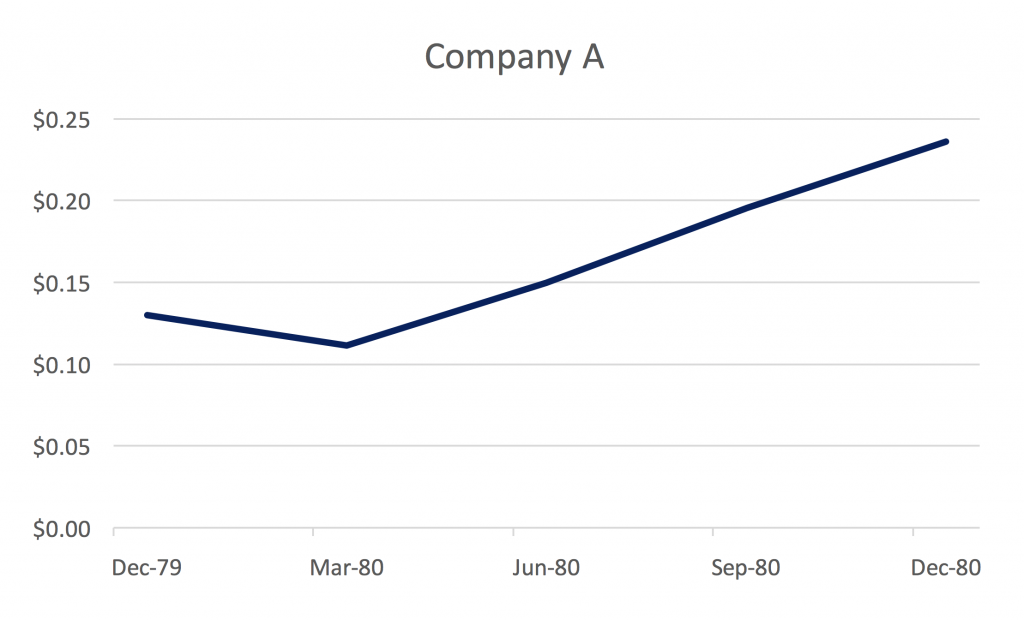

Let’s take the below stock price chart of Company A, which shows a company whose price went from roughly $0.13 to $0.24 in a year, an impressive 82 per cent gain for the year. You might think things are getting toppy, and that the stock has run ahead of itself. You sell your entire holding on the basis that the stock has now become overvalued, with the intention of buying the stock back once it becomes better value.

What just happened?

What just happened?

The investor sold the stock and implicit in this decision was the view that at some point the market would generate an opportunity to buy back into the stock at a more attractive price. This fits squarely into a buy low, sell high strategy, and it might seem like the investor has played this perfectly; after all, they’re sitting on an 82 per cent gain for the year! The difficulty is that while the volatility of the market can create opportunities to buy stocks at cheap prices, it’s also a double-edged sword in that it can cause seemingly overvalued stocks to stay overvalued for extended periods, particularly if a company is delivering consistently strong earnings growth.

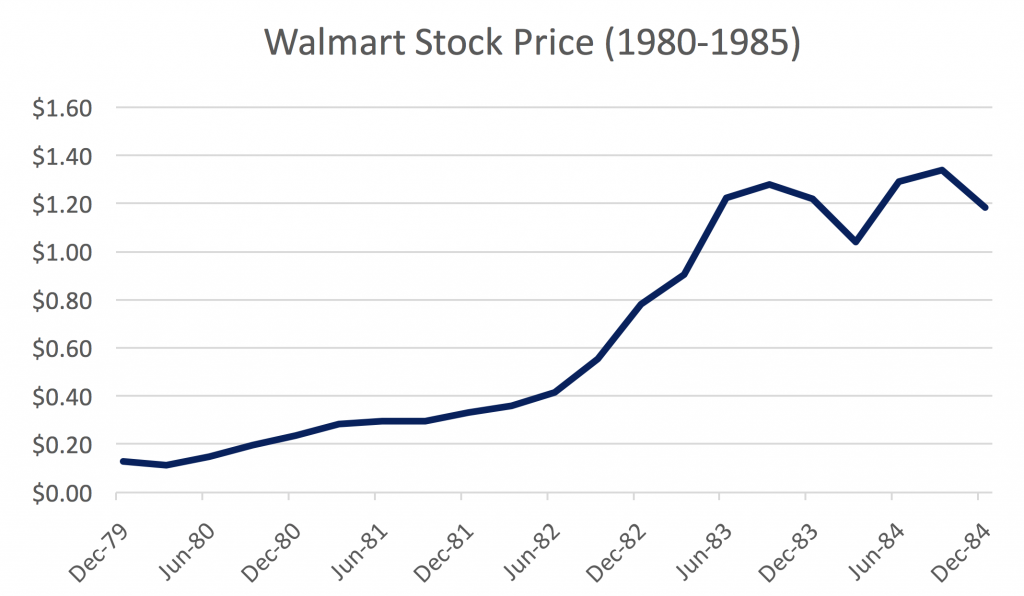

Company A is actually Walmart. If we look at what happened over the next few years, the stock price continued to rise. That initial $0.13 price at the start of 1980 went up more than 8x to $1.18 by the beginning of 1985, a 56 per cent annual return.

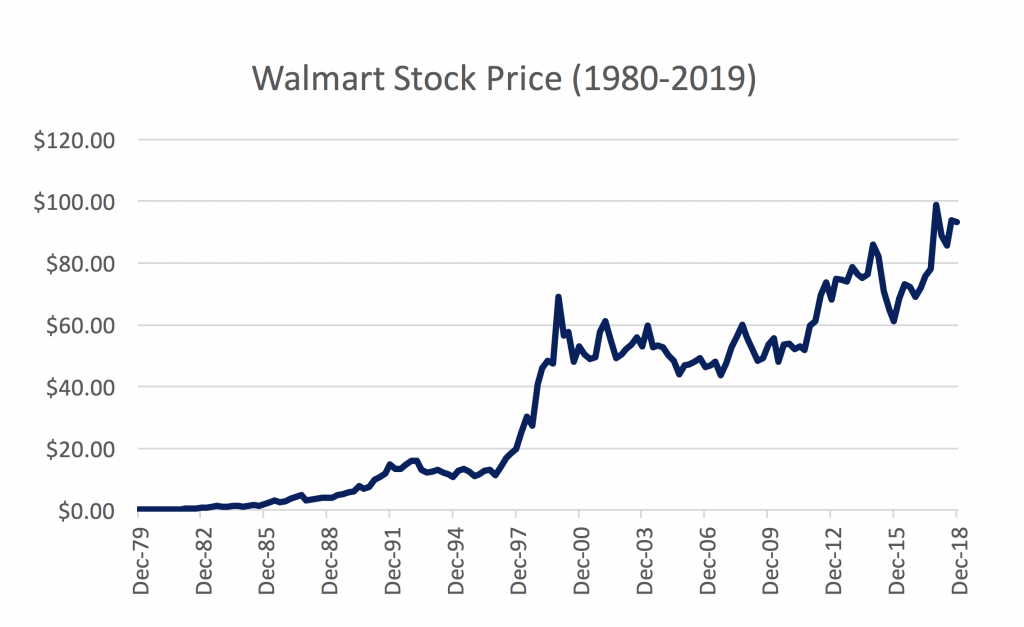

Walmart was growing rapidly during this period. The company had an advantaged business model with its Everyday Low Price (EDLP) strategy, and this model supported a large store rollout opportunity that underpinned the expansion of Walmart’s earnings power. This company was a compounding machine, deploying capital at high incremental returns. These businesses are rare and while there were plenty of opportunities along the way to sell at a handsome profit, it’s important not to lose sight of the forest from the trees. Walmart’s stock price between 1980 and 2019 grew at roughly an 18 per cent annual rate. If you’re able to invest in a business that can grow at 18 per cent annually for almost 40 years you will do very, very well.

The difficulty of timing these buying and selling decisions is: (i) we never know when a stock will become undervalued again (it could take days or many years); and (ii) the rapid earnings growth of these high-quality businesses means that a seemingly expensive price today might be bargain price a year or two from now. Investors could become anchored to what they thought represented an attractive price, but in reality this is a moving target due to the growth of the business. This creates the added difficulty of continually reformulating a view as to what price it would make sense to purchase the stock.

Time is the friend of a good business, and another benefit of holding for longer periods is the effect of any initial overpayment for the stock dissipates over time. In other words, as time passes, the initial multiple paid matters less; what matters over long stretches is the growth in earnings and cash flows of the business, and stock prices eventually follow this. The company grows into its valuation so to speak. While we would never view this as a justification for knowingly overpaying for a high growth business, it is perhaps comforting knowing that with a high-quality business that any initial mistakes around paying too high a price become less important over time.

In a similar vein, Buffett’s saying shouldn’t be taken literally, and a “set and forget” mentality is dangerous. The quality of the business in terms of the opportunity to invest capital at high rates of return and the defensibility of its earnings must constantly be pressure-tested.

The high-quality businesses of today might not necessarily be the high-quality businesses of tomorrow, and this is especially true in a world rife with internet-enabled disruption. However, at the same time investors must remember that arguably the greatest benefit you can derive from investing your capital is the wonderful effect of compounding; sometimes it’s best to find great businesses and heed Munger’s advice of not unnecessarily interrupting the effects of compounding.