Investor Insights

SHARE

All you need to know

At the weekend Warren Buffett led the annual shareholder meeting for Berkshire Hathaway, the company that he has led for more than half a century, in front of an unpacked stadium and without his business partner and vice chairman, Charlie Munger, at his side. That is not all that was different about this year’s event.

As many of you would know the Berkshire AGM is typically a weekend-long event in Omaha, Nebraska, that attracts over 40,000 attendees. Our New York-based analysts, George and Dan, have attended in the past and tell me that the centre (and the city) is packed as people move about stalls and stores and take part in various activities that all in some way link back to the various businesses that Berkshire owns. The main event is the hours-long Q&A session that Warren and Charlie conduct, responding to questions from attendees and those submitted by people around the world.

This year, however, the coronavirus pandemic necessitated major changes to the program. There were no live attendees – nor activities – for one. Secondly, Charlie was not able to travel to Omaha and did not take part in the meeting. Instead, Greg Abel, head of Berkshire’s non-insurance operations sat a safe more-than-1.5-metres beside Buffett. They spoke to a camera (supposedly also more than 1.5 metres away with cameraman behind) and answered questions from Becky Quick, a TV journalist from CNBC, who joined via video hook-up. But perhaps the biggest oddity was Buffett’s admission that Berkshire had not bought stocks during the market fall that started in February and extended into mid-March.

While Buffett spent considerable time outlining his “don’t bet against America” thesis, that has served investors well for over two centuries, through world wars and previous pandemics, and will again over the next two centuries; he stopped short of saying that now was the time to “buy America” again. In fact, he also spent a significant part of his presentation (do not look to him for tips on creating powerful PowerPoint charts) detailing the fallout from the Great Depression. In particular, Buffett pointed out to the “virtual” audience that after the US stock market fell from a record high in 1929, it recovered by about 20 per cent at around the day he was born in August 1930, then plunged by more than 90 per cent over the next two years. In the end it took more than 20 years for American stocks to return to the level that they were at when Buffett was born.

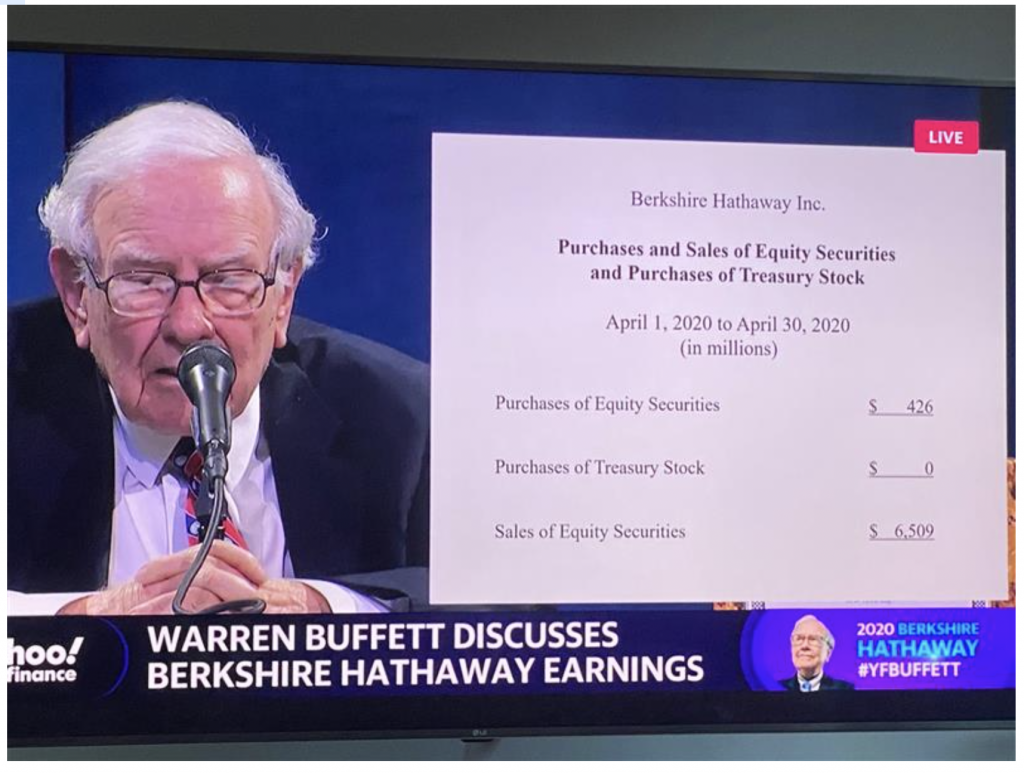

While Buffett’s words implied caution over the near term, his behaviour is the most telling signal. As I sat watching the live stream early on Sunday morning here in Sydney, I received a message from a senior colleague Amit Nath in New York. On our internal investment team chat forum, he posted the following message:

“All you need to know”;

and pasted the image below of Buffett and a table showing Berkshire’s equity purchases and sales in April.

In the month of April Buffett had overseen the sale of $6.5 billion of equity securities (mainly his investments in the four largest airlines in the US, despite his repeated claims over decades that the airline business is notorious for destroying capital, but that’s another blog post), and the purchase of just $426 million of stocks. To put that in context Berkshire’s equity portfolio totalled $181 billion at the end of March, cash and short-term government bonds exceeded $140 billion, and the market capitalization of the company is over $400 billion – in other words he virtually deployed nothing into the stock market in April. The picture for the March quarter is not much different, with around $4 billion of equity purchases but $2.2 billion of sales resulting in net investment in the market of less than $2 billion (or half of one percent of Berkshire’s market value).

I was recently reminded of the importance of the Stockdale Paradox in achieving long term successful outcomes despite the reality of nearer term challenges. Popularized by Jim Collins in his well-known, well-regarded book “Good to Great” he quotes former United States Navy vice admiral James Stockdale:

“You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end – which you can never afford to lose – with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they may be”

In his address at the weekend Buffett appeared to remind the investment community of the same.

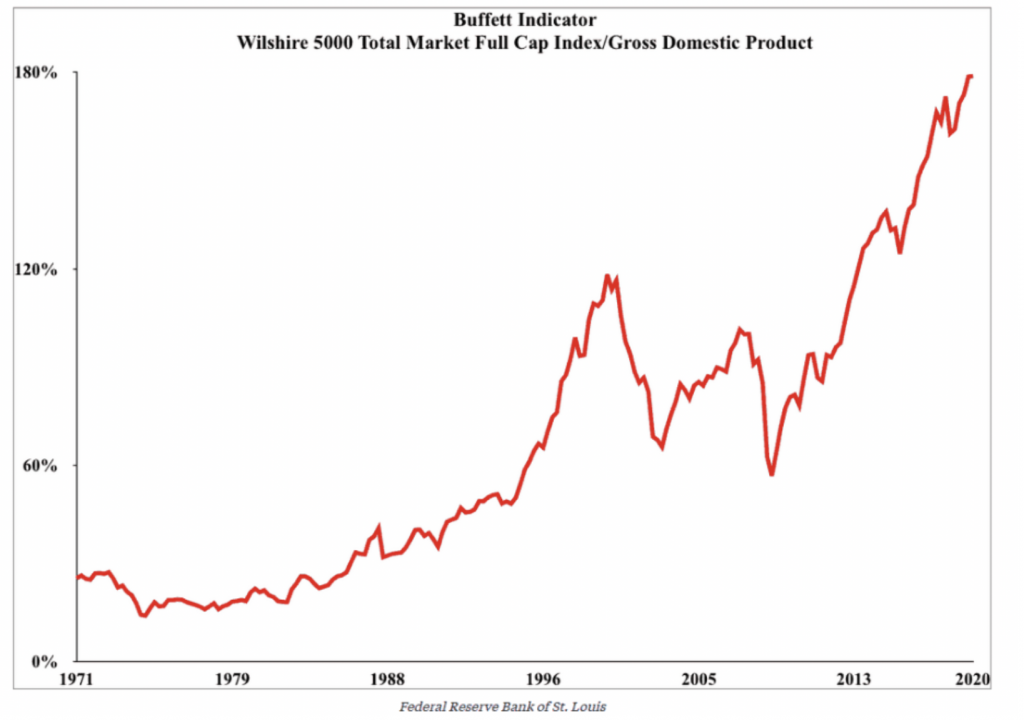

As surprising as Buffett’s words and actions may have been for a lot of people, viewed through the lens of the eponymous market indicator they should largely have been expected. In the week leading up to Berkshire’s shareholder meeting, the Buffet Indicator which is a measure of “overvaluation” of the stock market relative to the economy (calculated as the ratio of US stock prices to GDP) hit a record high and accelerated in recent months. This reflects the divergence between the direction of a stock market that has rebounded almost 30 per cent since its March low, and an economy that has rapidly deteriorated with GDP contracting almost 5 per cent in the March quarter – the worst since the Global Financial crisis and heading towards its worst reading in our lifetimes.

Reflecting similar caution, the Montaka and Montgomery Global funds have been positioned very defensively since mid-March. The net exposure in the long/short variable net exposure strategies is around 20 per cent and downside protection is enhanced by out-of-the-money put options (at small cost). The cash weighting in long-only strategies is more than 30 per cent.

At this time capital protection is our priority given elevated risks across economies and businesses, and stock prices that have quickly retraced much of their initial declines. Protecting our clients this way should be additive to long-term returns, but it is not without cost in the short-run. Indeed, as the stock market has rebounded in recent weeks the funds that we manage have not participated in gains to the same extent as various fully-invested equity market-wide indexes. Capturing these gains, however, would have required us to expose our clients to the continued possibility of significant downside risk, which is not something we are prepared to do. On the other hand, we will maintain the flexibility to own structural winners at attractive prices when risks have subsided. In this way, we are trying our best every day to face the “brutal facts of [the] current reality” but with a view that we will be prepared and positioned to “prevail in the [long-run]” on behalf of our clients.