Investor Insights

SHARE

Dollar cost averaging: navigating market volatility for long term success

Back in March 2022, Toby Roberts advocated for a dollar cost averaging approach to investing. Considering that The Montgomery Small Companies Fund has returned 11.19 per cent in the three months to 31 August, resulting in an outperformance of 8.97 per cent over its benchmark, I wanted to explore whether dollar cost averaging has provided another win for investors.

Back in March last year Toby wrote; “It is periods of uncertainty like this when investors may like to be reminded of the merits of dollar cost averaging. Dollar cost averaging is the investing strategy [equally] dividing up the total amount to be invested and periodically purchasing stocks, in an effort to reduce the impact of volatility and emotion on an investment. This is an investment strategy all Australian employees will be familiar with as it reflects the periodic contributions employers make into their superannuation.”

Importantly, a large lump sum invested at the beginning of a bull run in markets is always going to beat a dollar-cost-averaging approach, in which the investor holds a lot more cash until the amount earmarked has been fully invested. But during periods of volatility or major market declines, dollar cost averaging helps to ease the pain of falls while ensuring more units (of individual stocks or units in a managed fund) are purchased at cheaper prices as those prices get cheaper.

The Global Financial Crisis and the more recent COVID-19 pandemic were classic examples of events that inspired individuals to act in concert, producing the consequences of herd behaviour and panic.

Thanks to the indefatigable and unchanging nature of human behaviour, such events are reasonably frequent – indeed, they should be expected. Tey inspire fear and apprehension, which is why the dollar cost averaging approach is a good method to consider. Dollar cost averaging takes the emotion out of investing and helps to ensure sensible decisions are made while also providing some comfort when the tide goes out. And keep in mind bear markets are transitory.

Rather than be frightened of the inevitable volatility, the dollar cost averaging strategy will see you excited by periods of panic and looking forward to the cheaper prices that ensue.

For the U.S. S&P500, 2022 produced the seventh-worst calendar year return since 1928. But last year’s awful performance was a great thing for anyone who was putting money into the market on a periodic basis because bear markets are great for dollar cost averaging.

Before we examine the benefits of applying the dollar cost averaging approach suggested by Toby from March last year, lets revisit what the strategy is.

Dollar cost averaging, which can be applied to individual securities or stocks, index funds, and actively managed funds – the latter being my preference for young investors who have a great deal of time and very long runways for growth but no time to research investing in stocks directly.

Following an explanation of dollar cost averaging, we will explore a version I developed many years ago and first revealed to Ross Greenwood’s listeners when he hosted the 2GB Radio Money News program.

There are two ways to approach the stock market. The first, which is extremely popular, is betting on the ups and downs, to treat stocks like a gambler betting on black or red at the roulette wheel. The problem with this approach is that the stock market becomes a casino, and the house usually wins.

The alternative is to recognize stocks are pieces of businesses. Businesses create wealth by becoming more valuable because they generate growing profits, which can be distributed – even though they may not be.

Build value, ignore price

The process of a business creating wealth is a simple one, in theory. It’s much harder on the ground of course, requiring skill, intestinal fortitude, experience, teamwork, and a healthy dose of good fortune.

A company starts with some capital that has been contributed by its shareholders. If the venture is successful, the investment will generate revenues in excess of expenses, and a profit will accrue. This profit can then be distributed but may instead be reinvested, which builds on the original equity contributed and, therefore, the value of the enterprise.

Think about it this way; a bank account is opened with $100,000 and earns a 20 per cent return from the interest in its first year. Now you must agree that would be a very special and valuable bank account. In fact, given that interest rates on term deposits, at the time of writing, are about four per cent, you could sell the special bank at an auction and someone would bid a lot more than the $120,000 it now has deposited after the first year.

I wouldn’t be surprised if someone paid four or five times the balance of the bank account to own it. If they thought there was going to be a recession, or they thought interest rates might fall again, they’d be falling over themselves to own that special bank account for perhaps $500,000.

And if the bank account continued to earn 20 per cent annually for thirty years and the owner reinvested that interest, that bank account would have an equity balance of over $27 million and still be earning 20 per cent. Auction a $27 million bank account earning 20 per cent per annum and you can expect to see bids of more than $100 million (subject to interest rates at the time).

Can you see what I’ve done? I’ve just explained how businesses build wealth and how the stock market (the auction house) prices them.

The second approach to the stock market is to buy shares in those businesses that are able to sustainably generate high returns on their equity, and to wait for the wealth creation process to do its thing.

Of course, while you are letting the years pass and while the business performs its wealth-creation miracle, the auction house will be open. On some days, the attendees will be jovial and full of optimism, paying insanely high prices for the ‘bank accounts’ being auctioned. At other times they will be depressed and despondent, only thinking the worst.

Their moods however have nothing to do with the quality of that bank account that continues to earn 20 per cent per annum. Their mood is instead influenced by exogenous factors such as whether Donald Trump will be re-elected, or whether China’s unemployment rate is rising or falling. These things affect the ‘price’ of the bank accounts being auctioned but they have nothing to do with their ‘value’ or worth.

Dollar Cost Averaging

The dollar cost averaging strategy is what I call a ‘contrarian’ strategy. It forces you to be less optimistic when others are very optimistic while ensuring you are more optimistic when others are despondent.

The idea is to be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy, to quote one of the world’s most famous and successful investors.

On days when the stock market falls because everyone at the auction house is frightened, you simply need to remind yourself of the long-term wealth creation process of business, and apply dollar cost averaging.

We begin by setting ourselves the goal of investing a fixed amount of money – say $1,000 – every month or every quarter in either a particular stock, a portfolio of stocks, an index fund, or an actively managed fund. No matter what the market throws at us, no matter how crazy the auction house becomes, we simply keep investing our $1,000 monthly or quarterly – whatever was decided.

If the unit price of the actively managed fund is $2.50, the $1,000 investment will buy 400 units. If the unit price falls to $2.00, the next $1,000 investment will buy 500 units. And when sentiment in the auction house is overly optimistic and the unit price is $5.00, the $1,000 investment will buy only 200 units. With dollar cost averaging, more units are acquired at cheaper prices than at expensive prices but the strategy is always acquiring more units.

One benefit of the strategy is it helps the investor avoid being paralysed by fear. This can happen if an initial investment is made at $5.00 and then the unit price falls to $2.50. Many investors listen to the noise surrounding the events that caused the price drop rather than taking advantage of it. Instead of adding to their investment, they forget the long-term wealth creation process of business growth and run for the hills. The stock market is one of the few markets where shoppers zip up their wallets and run for the hills when the items are ‘On Sale’.

Some investors who buy at $5.00, panic when the price falls to $2.50. Being unable to bear the losses anymore, and fearing even greater losses, they sell at $2.50. When the market eventually recovers – it usually does – they miss out on the recovery. Other investors who buy at $5.00 are also petrified but do nothing when the price falls to $2.50. They simply wait until the prices recover. The problem with this strategy is that they have lost through the time value of money and they’ve not taken advantage of the opportunity to generate a profit from the recovery.

Dollar cost averaging seeks to mitigate the opportunity cost associated with doing nothing.

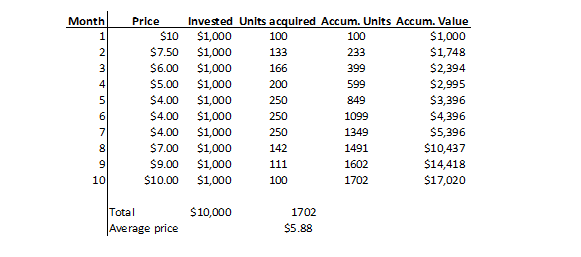

Let’s look at a ten-month period during which one thousand dollars is invested in a fund monthly, and the unit price of that fund falls from $10.00 to $4.00 and then rises back to $10.00.

Table 1. Dollar-Cost Averaging example.

If all $10,000 was invested at the beginning of the period, the value at the end of the period would be $10,000. And if all the funds ($10,000) were invested at the end of the period, the value would again be $10,000.

Because the investor took advantage of the auction house’s depressed sentiment during the period using the dollar cost averaging strategy, additional units were purchased while the units were at low prices. The $10,000 invested is worth over $17,000 at the end of the period because the average purchase price was $5.88 per unit and the units ended the period at $10.00.

Of course, it’s not always peaches and cream. If the unit prices had risen first and then fallen back to the starting price, the investor would have less value than investing the funds all at the beginning or at the end because they purchased additional units at higher prices.

But the end of the 10-month period doesn’t represent the end of the experience. As we demonstrated earlier, the process of business wealth creation takes years. Ten months is too short a time frame to consider the strategy a success or otherwise.

Provided the investor has picked a portfolio of select quality companies whose earnings march upwards over the years, or a fund manager that invests with discipline in such companies, the long-term value of the shares or units will rise, and so will the portfolio’s value.

Applying it to the real world

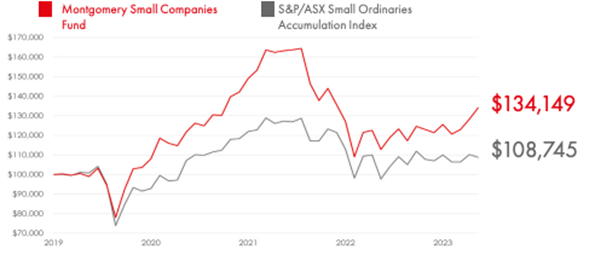

Figure 1. Performance of The Montgomery Small Companies Fund

Source: Fundhost

Source: Fundhost

I examined the outcome of investing $10,000 each quarter, since inception, in the Montgomery Small Companies Fund (the Fund) with the objective of comparing it to an initial investment of the same total amount as that which was invested through dollar cost averaging.

It’s an unfair comparison because the unit mid-price of the Fund at the time of writing is $1.223 versus the unit price at inception of $1.00. Moreover, the unit price has not spent a great deal of time below the $1.00 unit price at inception, which means there haven’t been a huge number of opportunities to acquire more units at prices below the inception price.

I have also ignored distributions. They are neither included in returns nor reinvested. The returns from investing all at inception or via a dollar cost averaging strategy would be even better than those described here.

Nevertheless, it remains an instructive exercise, especially for those who might be more nervous about investing and those who might fear the effects of recessions, war, inflation, and other exogenous factors on the performance of the stock market.

Keep in mind the period begins on 20 September 2019. The Fund was launched just a few months before COVID-19 hit. If you were ever going to have to endure an event that justified your fears about investing at the wrong time, it would be COVID-19.

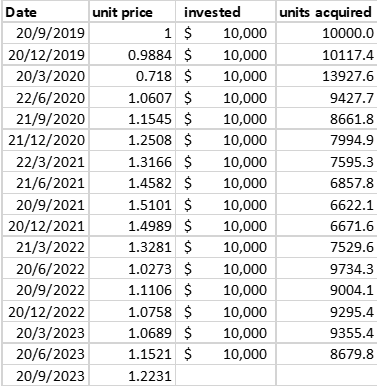

Table 2. Dollar Cost Averaging $10,000 into the Montgomery Small Companies Fund quarterly.

Given there were only two quarterly investment dates from 16 where the unit price was below the initial unit price at inception and that the unit price at the end of the period is higher than at the beginning, it is a reasonable assumption that investing all at the beginning will produce a better outcome than dollar cost averaging. Gary and Dom are doing too good a job managing the Fund for dollar cost averaging to be superior.

And that is evident in the results. Investing $10,000 each quarter resulted in an investment of $160,000 and the acquisition of 141,474.6 units for an average price of $1.13, clearly higher than the initial price of $1.00.

Had you invested $160,000 at the inception price of $1.00, the value today would be $195,696. The dollar cost averaging strategy resulted in $160,000 invested, which at the 20 September 2023 unit price of $1.2231, is now worth $173,037.

As I mentioned, it is an unfair comparison. And hindsight plays a big part. Because I am assessing the strategies today, I am comparing 16 investments of $10,000 with the same total amount at inception. I couldn’t have known at inception that investing $160,000 would be the appropriate amount to invest. I might have invested much less or much more.

The exercise, however, does demonstrate that a dollar-cost averaging strategy can ensure disciplined habits while also securing attractive long-term returns (provided the manager continues to do a good job) even if serious market setbacks have to be endured.

Obviously, it’s easy to look back at these things after the market has come roaring back.

Indeed, it is the ever-present possibility of market setbacks that renders the dollar cost averaging approach a comfortable strategy for navigating those adverse episodes in markets. Dollar cost averaging ensures more units are purchased as the market or the fund declines and aids a more rapid recovery as markets return to confidence. Down markets are a wonderful time to be long-term bullish.

Of course, if you have justifiable confidence in the manager’s ability to create wealth over the long term, then maximising an investment initially is the way to go. The caveat is that we just don’t know what could happen in between.

Portfolio Performance is calculated after fees and costs, including the investment management fee and performance fee, but excludes the buy/sell spread. All returns are on a pre-tax basis. This report was prepared by Montgomery Lucent Investment Management Pty Limited, (ABN 58 635 052 176, Authorised Representative No. 001277163) (Montgomery) the investment manager of the Montgomery Small Companies Fund. The responsible entity of the Fund is Fundhost Limited (ABN 69 092 517 087) (AFSL No: 233 045) (Fundhost). This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account your particular objectives, financial circumstances or needs. You should obtain and consider a copy of the Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to the Fund before making a decision to invest. The PDS and Target Market Determination (TMD) are available here: https://fundhost.com.au/fund/montgomery-small-companies-fund/ While the information in this document has been prepared with all reasonable care, neither Fundhost nor Montgomery makes any representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in this document including any forecasts. Neither Fundhost nor Montgomery guarantees the performance of the Fund or the repayment of any investor’s capital. To the extent permitted by law, neither Fundhost nor Montgomery, including their employees, consultants, advisers, officers or authorised representatives, are liable for any loss or damage arising as a result of reliance placed on the contents of this document. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.